I came across an extended excerpt from In Search of Captain Zero on my old website and thought I’d post it. The second half was cut from the book for space reasons, but you might find it interesting. (If you’ve read the book, maybe scan down until you get to election night, which is where it gets weird: So I pasted in the following to make it easier to find: It Starts To Get Weird.)

I sold it to Men’s Journal magazine in the spring of 1997. They paid me something around $3,000 (real money in those days, and which I sorely needed); then they decided not to run it. About a year later — after they published a piece I did called ‘The Caribbean on $25 a Day’ — I did a story for them about the murder of American rancher Max Dalton in Pavones, Costa Rica, by highly organized squatters and with the possible cooperation of the local government. At first the features editor accepted it gleefully, saying I’d probably win an award for it. Then, a month later, the publisher decided not to run it. (The bull shit I went through with Men’s Journal is in my last book, CYGAWA.)

As I figured out, both cancelations were because of my ‘political’ views of the countries in question, i.e., my bean spillage re some foreign policy issues. Here you go, and see if you are offended:

A Surfbum in El Salvador

Words & Pictures by Allan Weisbecker

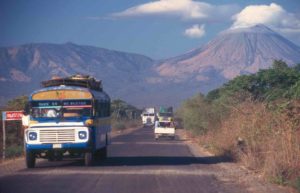

We find the narrator, along with his faithful canine companion, in the midst of a solo road trek through Central America in search of his old friend who disappeared in the area years before, and in search of waves to ride.

It was now late afternoon and James Ortega had been at El Salvadoran customs since 7 A.M., trying to get his truckload of office furniture released and on the road to San Salvador. A U.S. citizen of mixed Salvadoran/American parentage, James was finding his nascent office supplies business rough going, notwithstanding his fluent, nearly accent-less Spanish. He was in fact subtly rattled, chain smoking and continually mopping his sweat-streaked face as he waited to see if his latest mordida (bribe) would loosen up the slimy bureaucrat with the estampa — the omnipotent ink seal of corrupt approval. “I mortgaged my house for this business,” he muttered, then smiled thinly and tried to shrug it off.

There was another American at the customs and immigration compound, and I knew his curriculum vitae by his gringo-ized espanol, his baggy, low riding shorts, untied Air Jordans and assbackwards Dodgers baseball cap: he was a Los Angeles gangbanger, probably sent south to set up a drug or weapons deal with a Salvadoran cohort. (By rep, and pound for pound, Salvadoran street gangs in L.A. are more feared than their Mexican counterparts.)

In spite of our dissimilarities, and united by little more than our passport logos and familiarity with American Sports (and, hey, could our agendas in this alien land have been any different?), we three nortes — James in his sweat-stained button down shirt, dissheveled tie and Dockers, the gangbanger with his swarthily naked, musclebound torso and crazed, pupil-less eyes, and I in my huaraches and Real Surfers t-shirt — found ourselves in a loose, us-against-those-shit- for-brains-foreigners huddle.

Although James was obviously highly informed about the doings of the country, I avoided asking him about what I could expect down the road, not wanting to be subjected to the same sort of gloom-and-doom-you’re-gonna-die-real-soon bullshit I seemed to get whenever and where ever on my meandering path through Mexico and Central America I posed the simple query, What’s up?

I did ask him, however, how long it would take me to get to La Libertad, the sight of a world class but rarely traveled-to (I would find out why soon enough) right point break. James said I could make it in about an hour and a half, then nudged me aside until we were out of earshot of the gangbanger.

As it turned out, ready or not, here came the gloom and doom anyway. “Listen to me,” James said, sotto voce but with panic in his eyes. “Don’t tell anybody your business here.”

A bewildered “Wha-what?” Was all I could come up with.

“That guy (the gangbanger) knows where you’re going now.” James lit another cigarette with a trembly hand.

“I really don’t think he gives a shit, James,” I said.

“Look…” He said, inhaling deeply. “There’s a certain… tension in this country.” No shit, I was thinking.

#

Three hours after pulling out of customs, and with the last blush of dusk fading somewhere behind

me, I found myself yelling out the rig’s window as it rattled down a traffic-less, rutted dirt track skirting a plumbline drop of a half kilometer to the sea, “Yeah, James, it might be an hour-and-a- half fucking drive to La Libertad, IF THERE WAS A FUCKING ROAD TO DRIVE ON!”

I switched on my headlights for the first time in over six months — I hadn’t driven after dark since crossing the border at Tijuana. My hard and fast rule throughout the journey had been to find a safe place to stay well before nightfall. I had broken that rule and now here I was in pitch black on a highly questionable road in a country where over the past two decades so many people had disappeared without a trace that the verb itself in local gringo usage had made the grammatical leap to transitive, to mirror the nuance of the Spanish; as in “Jose’s family [was disappeared] last night, probably by a right wing death squad.” And tens of thousands of others, some U.S. citizens included (advisors, businessmen, nuns, freelance writers; plus a whole Dutch film crew), had been just flat out slaughtered.

Thing is, I should have known better. If I’d learned anything over the past months, it was that no one, no one south of the Mexican border has any idea how long it takes to go from anywhere to anywhere else. And at best — even if it had only been 90 minutes to La Libertad — I’d have been cutting it close. I’d been fantasizing about that goddamn point break, was what I’d been mindlessly doing, envisioning myself in the lineup at first light. What I should have done was stay at El Salvadoran customs overnight. (Customs, along with airport parking lots, are safe, if insipid, places to overnight in a pinch Down South.)

Lights up ahead, finally. Ok.

La Libertad, El Salvador. Half a year in Latin America had prepared me not a whit for this derangement: nothing as purposeful or organized as a riot, more a randomly seething mass of hard core, down and dirty humanity, blocking my way in garish pools of streetlight, then parting sullenly sideways into the shadows, with individual, covetous stares at La Casita Viajera — my little traveling house — and the imagined goodies within; and someone’s bad thoughts actualizing in the banging of a fist on the side of the rig (perhaps to see what would fall out) as it jostled down the narrow, one way descent into more of the same.

At some point in my tour through town I started considering my situation borderline serious, verging on actually serious.

Okay. A gas station up ahead, brightly lit and clear of the worst of the barrio bajo chaos, a couple guys busily closing up, it looked like. Pull in to fuel up and regroup, think this over…

But one of the guys was waving me through, saying the pumps were locked and indeed the lights went off. I stopped anyway, offering fifteen colones — a couple of bucks — to park for the night. Twenty, he said. Ok, I said, if you put the lights back on, all of them — I wanted that gas station to look like high noon in Alabama. We settled on twenty-five and I was soon ensconced under the glowing Chevron sign.

The rest of the night didn’t go all that well. My dog, Shiner, leashed to the back of the rig outside, kept up a continual snarling racket as assorted street goons made tentative forays. (It eventually occurred to me that the wash of light I’d so cleverly contracted for amounted to a neon arrow pointed at all my current worldy possessions, with the caption “COME AND GET IT!”.) But after two gunshots boomed and echoed down the street, I brought her inside, locked up, set my jalapena spray and fish billy by my bunk, and cranked up the “Miami Vice” soundtrack tape I used to play for inspiration when I was writing for the show in its first season — a move I soon abrogated as being ridiculous and embarrassing. What was I thinking? That Donnie and whatsisname’d come barreling on screen to my rescue, Brem 10s outstretched in choreographed combat stances, yelling Freeze! Miami Vice! (yes, I had actually penned those words) if the shit hit the fan? Jesus, was I that jangled?

With the door shut, not a breath of breeze stirring, and two hot, keyed up bodies in the cramped space of La Casita, the temperature rose steadily, no doubt well into triple digits. I covered the two of us with towels soaked in the ice water that had collected in the fridge, turned on both 12 volt fans and settled in to a long, sweltry, paranoid wait for morning, glad for the steel bars I’d through bolted over the windows and forward hatch, lock lugs on my Goodyears and alarm system up front.

There’s a certain… tension in this country.

Eventually I dropped off into unconsciousness, only to be startled awake by some miscreant banging on the back door and — probably inspired by my Empire State tags — yelling something about “Nueva Jork.” He sounded more drunk than dangerous so I ran him off by swinging the door open to give him a gander at Shiner’s dentals.

First light came like a reprieve. The threat of dawn had cleared the streets as swiftly and completely as if La Libertad, El Salvador was a southern stronghold of Hispanic vampires.

I fired up the rig like a man on a mission, which I in fact was.

Find that point break.

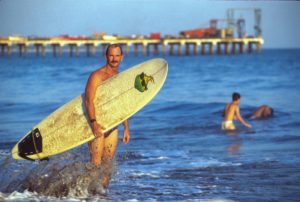

I did, and rather quickly, simply by making every turn that led downhill until I found myself with an unobstructed water view. There, in the distance to the west, past a long steel pier piled end to end with fishermen’s lanchas, it was. Known simply as La Punta — The Point — it indeed had the jutting rock configuration of a world class set up. And it was breaking, long lines bending into the bay and peeling across the seascape with machine-like precision. Just two guys out. The sun rising in a cloudless, pellucid pink sky behind the steel pier.

There’s nothing like your first wave at an uncrowded, warm water point break to impart the proper perspective on things. In truth, the last twelve hours had rattled me, rattled me to the point where I’d been wondering, truly wondering, what the fuck I was doing here. But pulling out of that first razor-edged, head high zipper at The Point, the answer was obvious: this is what I was doing here. Last night wasn’t that big of a deal, I was thinking as I stroked back out. What had been my problem? Spend the night way back at customs? Was I nuts?

What, me worry?

#

“Coupla things you ought to know about this break,” Tim from San Clemente cautioned as we

waited out a lull. “There’s a rock on the inside that’s a factor at this tide and swell size.” I’d already figured this out, having barely avoided a head on collision with it on my first wave. “Also, it’s best not to wear a watch or jewelry surfing here.” This was not the sort of advice you normally hear in a lineup, and I quickly sensed it wasn’t fashion-related. “Locals’ll hop that wall you have to walk along to get to the paddle out spot and rob you before you hit the water.”

A set popped up and I gave Tim his choice of waves, even though I’d drifted to the prefered inside position. Didn’t matter, they were all good.

Paddling back out together, I mentioned to Tim that I’d had a slightly uncomfortable night parked in town. Tim shook his head. “Be careful in town. Dress as grubby as possible and don’t carry anything of value, cameras or whatever. Two surfers got held up last week, one in broad daylight, both at gun point.

“Most of the locals here are cool,” Tim said, then grinned. “But there’re also a bunch that’ll kill you in a heartbeat.” His grin widened. “By the way, your timing is good. There’s an election next weekend. Word is it might get a liiiittle tense around here.”

We both laughed and I reflected on the contrast between Tim’s happy-go-lucky, borderline goofball deportment at the level of tension in El Salvador, and James’s, which amounted to borderline panic.

Again, surfing’ll take the edge off almost anything.

#

Bob Rotherham was probably the best known expatriot surfer in Central America; his rep was common knowledge amongst traveling surfers Down South. He’d come to El Salvador in the early 70s and wound up settling in La Libertad, marrying a local, starting a business, the whole expat nine yards. I wanted to sit down with the guy, drop a few names, shoot the breeze, maybe find out some things.

It took me all of about a minute-and-a-half to locate Bob; in fact, I’d parked my rig right in front of his restaurant at the base of The Point.

As we made ourselves comfortable on his sea view veranda, I asked Bob what it was like in El Salvador back in the early days, when Central America was still largely unexplored, by surfers or anyone else from up north, maybe apart from CIA spooks and their ilk.

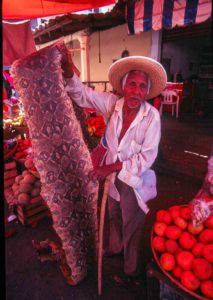

Bob waxed rhapsodic about that golden era, when La Libertad was a free zone, a wild and wooly port town of fleshpot guzzleries, brothels and itinerant merchant seamen from far and wide; plus a small, tight knit cadre of serious gringo watermen, here for the wave at The Point. These were the days before la problema. La revolucion. The civil war.

Bob had lived here — even prospered here — through all of it; the death squads, the desaparecidos, the murderous mayhem that had cost uncountable lives. How had he dealt with it? “You learned to live around it,” Bob said casually. “You hardened yourself to it, even saw the humor, black though it was, in some of what happened.” He described how the FMLN — the anti-govrnment guerillas — had stormed La Libertad just before the cease fire in 1992. He pointed out where the mortar implacements had been set up in the hills to the north, and where some of the rounds had struck — one on the beach in front of the restaurant.

“The FMLN don’t surf,” I said, refering to Robert Duvall’s classic line, “Charlie don’t surf!” in Apocalypse Now.

“Yeah,” Bob said, grinning. “It was right out of that. In fact” — here, his grin widened — “there was a hotel full of surfers just down the street that took a direct hit from a rocket launcher.”

“Jesus. What happened?”

“For some reason, it was a dud. They found the thing later, imbedded in the wall behind their room like some big, nasty dart.” Bob shook his head and grinned. “You had to laugh at stuff like that.”

“Guys just kept coming down to surf The Point, revolution or no.”

Bob nodded. “Guys with nicknames like ‘Pinhead,’ ‘Cosmo,’ ‘Brown Dog.’ This guy, Roger something, carted a mess of bizarre radio gear with him. He was trying to contact extra-terrestrials.”

“What’s it like now that the civil war is technically over?”

“The downside to the treaty is that there seems to be more violent street crime. It’s actually more dangerous here now.”

At least the thugs didn’t have mortars and rocket launchers, I was thinking, or rather, hoping. That’s an improvement. “Listen,” I said, finally getting to the deep motive behind my talk with Bob. “Where do you suggest I overnight around here?” The quaint little area of seaside restaurants and pensiones on the peninsula at the base of The Point had the feel of a stronghold, but just a block inland the barrio bajo began, and spread inland and up and down the coast like enemy territory.

Bob had to think this over. Almost all the visiting surfers at La Libertad flew or bused in and stayed in the pensiones. Arriving by rig, my dog and I were a rarity. Where to put us was a good question.

Meanwhile, a fellow came over to our table and spoke briefly to Bob. A gringo in his early thirties, his round glasses, pallor and pleasantly studious mien suggested a teacher, an academic of some sort. His name was Erik. “Not a surfer,” I said, as Erik hoofed it across the downstairs patio to the road.

“Nah,” Bob said. “An agricultural advisor with some international agency. Arrived from up country a couple days ago.” Bob then suggested I talk to a woman who ran a nearby hotel about staying on her property. It was fenced and shaded and would probably be safe. An easy walk to The Point. Great.

We then got onto the subject of owning a business in El Salvador and the future of the country as a possible destination for straight tourism. Bob thought it might happen — it would depend largely on whether or not the Salvadoran government started slaughtering everybody in sight again — and hoped that it would. His business was 90% local tourists from San Salvador now, the remaining 10% largely visiting surfers. Then he said something that made me laugh. He said he didn’t understand why more surfers didn’t come down here, adding that “This place is a surfers’ paradise.”

The great wave at The Point notwithstanding, I reminded Bob of a few things that might have slipped his mind. Like the two separate incidents of surfers getting held up at gunpoint a couple blocks away last week, one in broad daylight; like the fact that you didn’t want to wear a watch surfing for fear you’d be done in before hitting the water; like the possibility that the peace would be broken and you’d find a bazooka round stuck in your hotel wall; like the fact that it was more dangerous to be here now than during the bloodiest revolution Central America had ever seen. Like the fact that there was A CERTAIN GODDAMN TENSION IN THIS COUNTRY!

Little things like that.

I don’t remember the exact words to Bob’s response to my good-natured tirade, but they reminded me of the all-time best last line in the history of the movies: at the end of Some Like It Hot, when Joe E. Brown discovers that the love of his life (the Jack Lemmon character) is actually a man in drag. The line, of course, is, “Well… nobody’s perfect.”

#

Been here nearly a week now (it’s election day minus two) and have come to the conclusion that in an assbackwards way, Bob is right, but it’s precisely the unique perils of living and surfing here — the concomitant unity among the handful of surfers in La Libertad — that make it at least close to being a surfers’ paradise.

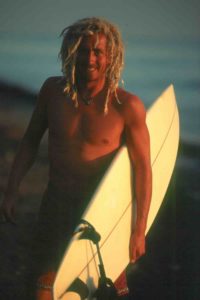

They are a good bunch. Tremont, for example. We were sitting on the steps at the swimmers’ beach a couple days ago, having just come in from our morning session. We were reminiscing about places we’d been, waves we’d ridden. As always, Tremont was making me giggle. He’s a big, strapping young guy — not yet out of his twenties — with blond dreadlocks flowing in a matted tangle most of the way to his butt. A very surfy fellow. And he’s French: his accent is exactly that of Peter Sellers as Inspector Clouseau. “Room” is “rim,” “phone,” “fun,” “bomb,” “bim” (it was a circuitous conversational route I steered, getting him say that word; then I howled), and so forth. The ac-CENT invariably falls on the wrong syl-LABLE. This is what makes me giggle; a dreadlocked Clouseau who surfs.

Tremont was rhapsodizing about Brazil — he’d spent most of the previous winter there — not so much for the waves, but for the fact that “Zere are twenty wee-MEN for each one of us.” He sighed and shook his head slowly, eyes glazing. “How zees could be, I wass not unnerstanding, Al- LAN… but eet wass very good.”

Erik joined us on the steps as Tremont was saying, “You must have zee ba-LANCE in your life, no?” Erik had been mostly keeping to himself; no one would see him for a day or so, then suddenly he’d just unobtrusively show up.

Tremont went on: “For six mahnts you do your work for zee mo-NEY to do what you love.” Surfing, of course. What Tremont did for the other six months was this: he strolled the beach at St. Tropez, selling espresso coffee from a backpack canister. (“Low, how you say, over-head; eet ees all prof-EET.”)

“Let me get this straight,” I said. “When you’re not on the road surfing, you’re hitting on topless women in the south of France.”

“Last sum-MER I haf to hire a West Indee-AAN fel-LOW so I can haf a leetle more time for zat,” Tremont said with a shrug indicative of helplessness of his plight.

“So, Erik, what did you do last night?” I’d heard enough about Tremont’s life. I was also curious about Erik’s doings.

“Well, I met four American girls,” he said, in his characteristic low key manner. “We had dinner and went for a swim.” This perked Tremont and me up. La Libertad wasn’t exactly crawling with on-the-loose women — which was one reason it fell just short of being a surfer’s paradise. “It’s not as great as it sounds,” Erik added quickly. “They’re Christian missionaries.”

“Shit,” I said. “Nuns?”

“Not exactly, but close.”

“Ahhh…” Tremont said, sensing hope. “So zey haf not yet signed zee pa-PERS, eh. Zees could be Impor-TANT.”

“Maybe one of ’em joined the church because of a problem with nymphomania,” I added.

“And is ripe for a backslide.”

“What does zees mean?” Tremont wanted to know. I told him; he nodded pensively. “Zees would be good, too.”

Erik looked at his watch and got up. “I’ll bring them around tonight if you want.”

“We want,” I said. As Erik strode purposely off, glancing at his watch again, I said, “What does he have, some kind of appoint- ment?” Tremont shrugged.

“I think Erik’s a spook.”

Tremont squinted at me in non-comprehension.

“A spy. A secret agent.”

Tremont laughed. “No. Think about it. What were his last few jobs? A refugee camp in Thailand, screening

Vietnamese who wanted to emigrate to the U.S.; then he goes to Indonesia, teaches English there, he claims. Tell me, does Erik speak Indonesian?” Tremont spoke some Indo and had thrown a few words at Erik the day before.

Tremont shook his head. “I wass surprised. How can you teach Eng-LISH if you don’ speak zee oz-ZAR lan-GUAGE?”

“And now he shows up in El Salvador as an ‘agricultural advisor,’ during the week of the first election this town’s had since the cease fire. I bet he doesn’t know one end of a cane field from the other.”

But Tremont’s mind was wandering. “May-BE zey kill zee boy ba-BIES, eh?”

“What?”

“Een Brazil.”

“Goddamn it, the guy doesn’t surf. What could he possibly be doing here?” Tremont laughed again.

“I’ll tell you what he’s doing here,” I said, having gotten on a roll. “He’s here to help the right wing government motherfuckers fuck around with the election.”

I’d also come up with who Erik had reminded me of: A guy Christopher and I had run into in Panama while outfitting Ensenada for her doomed run nearly twenty years before – it was during the time of the Canal Treaties fiasco, when President Jimmy Carter was lobbying for an early reversion of control of the Zone to the Panamanians. Derek was cut from the same mold: same studious, low key act (he’d even worn those round, wire

glasses) and shifty resume. We’d met him through our Panamanian government connection, then dictator General Omar Torrijos’ head of security and liaison to the various spooks, drug runners and all-around miscreants who kept Torrijos’ personal coffers flush. The liaison himself was a classic Third World slimeball, an arrogant, dipshit fanfaron whom we called to his face Manny; but because that face was so stone ugly and deeply pockmarked, everyone privately referred to him as The Pineapple. At the time, and because of the severely unofficial nature of our dealings with him, I never bothered to commit to memory The Pineapple’s last name. However, when he took control of the country a few years later I saw his distasteful visage plastered on the covers of various magazines and newspapers.

The Pineapple, our Panamanian go-to guy for everything from official protection to clandestine airstrips to head stash to high-end whores, was Manuel Noriega. It was through Manny The Pineapple that Christopher and I were introduced to this guy Derek so strongly reminded me of, who turned out to be CIA. Christopher and I had a few drinks with this fellow at the Holiday Inn in Panama City, and as the night wore on and the booze flowed, his view gradually surfaced of why the United States had agreed to return the Canal to the Panamanians before the treaty required it to do so.

According to his “sources”, General Omar Trujillo (the then dictator of the country) had contacted David Rockefeller, the CEO of Chase Manhattan Bank, and informed him that if we didn’t immediately return the Canal, Panama would default on the half billion dollar loan Chase had made it. Chase’s financial predicament at the time was such that this would have resulted in the bank going under, which in turn would have lead to general economic chaos in the West. Rockefeller then informed Jimmy Carter of the threat; fearing the consequences, Carter agreed to cough up the Canal. “General Omar really pissed off certain elements in the U.S. government,” this fellow told me with a wry grin. An interesting assertion, as it turned out: Trujillo would soon die in a plane crash of suspicious origin.

In fact, and in light of subsequent events in Panama and elsewhere since Carter’s Canal Treaties rollover, the fellow’s theory has begun to look downright reasonable. At the time, we figured him just another unbalanced Down South spook; there were so many. (It’s now pretty much common knowledge that the CIA killed Torrijos.)

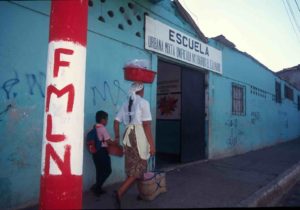

Whoever painted the FMLN’s colors on this pole was risking his life. La Libertad was a hairball place to voice freedom of expression.

Derek did not show up that night with the Christian missionary girls. The next and only other time I saw him was on election day, striding determinedly somewhere and looking at his watch. Although he claimed he was in La Libertad for the sun and salt air, he was as pale as the day I first met him at Bob Rotherham’s restaurant. I don’t recall once having seen him on the beach.

#

It Starts To Get Weird

It’s now late at night on election eve in and as I sit physically hunched and psychologically bent at the settee in La Casita Viajera with the rising wind and approaching thunder beginning to subsume the vocals of an acre of boisterous krauts belting out “Ode to Joy” on the stereo — a usually reliable palliative, failing tonight — I’m trying to make sense of certain things, certain occurrences, doing my best to separate paranoid, nightmarish fantasies from reasonable scenarios; the pot I smoked with the crew down at Tim’s bunker of a hotel a little while ago is definitely not helping matters.

The first odd thing happened directly after I came ashore. I was sitting on the steps where Tremont and I had our conversation when this nattily dressed Hispanic fellow joined me and started talking in rapid Spanish, some of which I didn’t quite catch. The conversation seemed at first to be of little consequence: he blabbed about how much he liked the States and where he’d been up there and how nice the American people were and so forth. Then a few questions: did I like El Salvador? — yes, I said, very much — how long was I staying? — not sure, I said, depends on the surf — where was I going next? — south, I said, to Nicaragua. He then asked me what I did for a living. I was getting tired of the banter and of his rapid speech, so I’d shrugged and said with a politely dismissive tone Nothing at the moment; I’m just traveling and surfing.

Then he handed me a business card. I got no more than a glance at it — something about an international election committee with a Washington, DC address — before he seemed to change his mind about giving it to me and snatched it back. If there’d been a name on it, I don’t recall it; my recollection is that there wasn’t. He then patted my shoulder, bid me be careful and have a safe trip and ambled off towards town.

There’d certainly been nothing overtly menacing about the fellow or the conversation, but still, the episode — the questions, the business card with the election reference — was vaguely disquieting.

Another odd thing happened when I went into town to run some errands. I no longer think twice about making daylight forays into the barrio, although I make sure to dress even grubbier than usual and carry no more money than I’ll need. Today, however, I’d wanted to change some dollars at the bank, and a local buddy, Roberto, offered to go with me, warning that street punks would sometimes stake out banks, hoping to waylay anyone emerging with bulging pockets.

With the election only a day away, town was really heating up. There was a lot of red in evidence on the streets: banners, flags and head and armbands — red is the FMLN’s color, a carryover from their origins as “hard core” communists. (They’d been Cuban and Soviet backed, according to U.S. “sources” — as always, the yanqui excuse for violent meddling.) Bullhorns blared, candidates’ faces grinned slimily from posters on every telephone pole, graffiti-ed party slogans helloed from crumbly adobe walls. A general sense of excitment, if not agitation.

The air-conditioned bank was cold as a meat locker. As I sat down across from a smiling young woman at her desk, I erupted in a sneezing fit so violent and protracted that we both laughed. This led to the usual small talk about the hot weather and where I was from and how cold it was back there now (“but no colder than your bank,” I quipped) and whether I liked El Salvador, while she took down my particulars — my passport number and where I was staying and what I did for a living. I was rolling — my Spanish had improved dramatically over the past months — so I continued the dialog by asking if she was planning on voting tomorrow.

The question stiffened her and made her look away as if I’d asked permission to crawl under the desk to see what was going on up at the other end of her leg from her foot. After a long, very uneasy moment, she picked up my papers and little stack of dollars, got up and without a word strode over to another bank officer’s desk. She put my papers in front of him and began talking to him, her back to me. It seemed a needlessly long conversation considering the simplicity of the transaction; the man glanced over at me twice while looking at my passport. He then handed everything back to her, except a carbon of my particulars. She returned, laid the colones and my receipt on the desk, then walked away without looking at me. The man behind the desk was looking at me, however. Very pointedly so.

Roberto was waiting for me outside in the blast furnace heat and as we weaved our way through the teeming barrio, I described what had gone down in the bank and asked what he thought it’d meant. He shook his head gravely, saying he didn’t know, then warned me to be careful, very careful, adding, “Stay off the streets tomorrow, even in the daytime.”

I had some shopping to do and felt it weird and unnecessary having Roberto shadow me around as a bodyguard, so I thanked him and went off on my own. A half hour or so later, having loaded up my backpack with staples, I cut down a narrow side street toward The Point to find it mobbed with milling, chanting, thoroughly pumped Salvadorans. The crimson colors of the FMLN were everywhere: I’d stumbled upon their election headquarters. Although frenetic, the general mood seemed upbeat — I did not perceive it as threatening — so I eased my way through the throng until I reached a dilapidated old building plastered with election posters and graffiti and festooned with banners and flags bearing the FMLN logo.

A coterie of zealous electioneers was dispensing literature and calling out to passersby from the steps and I made eye contact with a young man who seemed to be a leader; his grin was so huge and genuine and so completely disarming that I immediately knew I should talk to him. His name was German (Pronounced Herr-man).

I’d already learned from Bob Rotherham that the election was a local one and pitted the FMLN — the former leftist guerilla movement, which had been given political legitimacy via the 1992 treaty — against the National Republican Alliance (ARENA), the right wing government party that had been responsible for the tortures, mass murders and disappearances during la revolucion, the civil war.

Although there are gray and still darker-hued areas of human conduct even within the ranks of rightful causes, in the Salvadoran civil war, ARENA, without question, had been the bad guys. In talking with German, and surrounded by FMLN Salvadorans — many, no, most, no all of whom had undoubtedly lost family or friends during the conflict — I had to deal with a nagging dose of yanqui guilt. Guilt based upon the fact that the Reagan and Bush administrations had, overtly, through mendaciously legitimized foreign aid (“There has been sufficient progress in human rights, land reform and the initiation of a democratic political process to qualify El Salvador for continuing blah blah blah” — blatant, incredible lies), and covertly, via the usual clandestine and vicious modi, supported ARENA’s psychopathic leadership throughout the conflict.

I told German — or tried to tell him, for in my unease my Spanish seemed to be abandoning me — that the American people had supported his cause, even if the American government had —

German interrupted my inept (and of course not altogether candid) ramblings with a smile and a pat on the shoulder. He understood, he said, and had faith in the ultimate wisdom of the American people. (By God, that’s more than I can say, I was thinking.)

But German was young, maybe too young to have fought in la revolucion, and had probably not been personally subjected to the nocuous repercussions of American “aid.” Also there in front of FMLN headquarters, however, were older men, men in their thirties and forties, men with hard eyes that had seen a world of pain and suffering and death, and they were not smiling and they were not patting me on the shoulder and telling me they understood and had faith in the wisdom of the American people. And I was glad that over the hubbub of their new-found political freedom they had not been privy to my self-servingly apology for my country’s collusion in their national tragedy. You cannot so easily fool men such as that.

These men, I suspected from the brief, stolid looks they cast in my direction, saw me for what I essentially was: a harmless and insignificant yanqui dilettante who politically, morally, and probably otherwise, had his head up his ass. But on the other hand, some may have borne me a grudge, not so much based upon the accident of my citizenship (of a former, and who knew, possibly current, enemy), but upon the gall I’d evidenced by my presumptuous intrusion into a world they’d paid so dear a price to fashion. I would have harbored such a grudge, I was thinking, as I made my way back to the safety of the stronghold at the base of the peninsula below the surf break known as The Point.

#

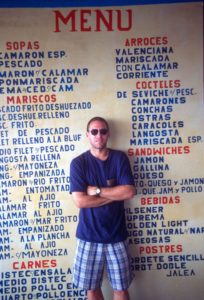

“So, Erik,” I was saying as we sipped fruit smoothies at the little seaside restaurant across from my niche in the hotel courtyard earlier this afternoon, about an hour after my visit to FMLN election headquarters, “Are you a spy?”

Locals and travelers visit the rig. On the left that’s Flavio, Luis (Panamanians), and Tim from San Clemente.

I’d happened upon Erik after his two-day absence from the beach scene and had suddenly been inspired to do some subtle grilling, possibly find a hole or two in his unlikely story. (Although he’d claimed he was in La Libertad for the sun and sea air, he was still pale as the day I’d first met him in Bob Rotherham’s restaurant; I could not recall having seen him on the beach.) The subtle approach having failed, my impatience had gotten the upper hand and I’d thought to bushwack him by blurting out the essence of the matter, maybe catch him off guard.

Well, I caught him off guard all right. His initial response to my query was physiological: he actually blushed; but it seemed a blush of embarrassment at so strange and aggressive a question, not of guilt or chagrined surprise at having been found out. This was perfectly in keeping with the innocent, almost naive demeanor he’d evidenced from the first.

Nah, probably not a spy, I was thinking. Whoever heard of a spy that blushed? Besides, his stuttering bemusement had a genuine ring. And then, after I’d explained the basis for my bizarre (as it was starting to seem) suspicion — his background, his unlikely presence at election time, his mysterious in-country peregrinations, etc — he seemed to puff up a bit, as if his own image of himself had taken on a whole new import: all that was now lacking was a bullet- proof Astin Martin with revolving license plates and explosive passenger ejection seat for him to buzz around La Libertad in, a foiler of apocalyptic plots, a seducer of slinky counterspies — if not Christian missionary girls.

But still, there was the acid test, and I’d come prepared to administer it: I held up my camera with a grin. Would he mind if I took his picture? Erik smiled shyly and I thought I’d detected another reddening of his cheeks. I don’t believe he’d even connected my photographic proposal to the spy question, which was a further indication of the depth of my position in left field.

Nah, definitely not a spy, I was thinking, as I had him stand in front of the menu printed on the wall to impart a sense of place to the shot; he said Cheese and that was that.

“So,” I said as we returned to our seats, “basically what you’re here for is to tell the Salvadorans that if they cut down all the trees, there won’t be any trees left?”

“Basically…” Erik said, after a mulling pause, “that’s right.”

#

Just after dark earlier tonight a few of us got together to go into town for dinner: Tim, Tremont, another gringo named Andy and myself, itinerant surfbums all. Four being a borderline minimum for a safe and secure nocturnal barrio sally, Shiner accompanied us also, to walk point. We meandered east down the well-lit streetlet of our oceanfront stronghold, greeting with casual equanimity the shopkeepers we’d come to know, then turned inland, instinctively closing ranks as the pavement, illumination and our collective sangfroid all at once deteriorated; the barrio bajo, with its ragtag, raptorial denizens, had that abruptly begun.

The usual cluster of shirtless young malvados was absent from the doorway halfway down the first block where invariably they hung out in idle vigilance, like vultures on a wire. In fact, the street yawned dim and empty all the way up the hill to its terminus overlooking the sprawl of the town.

“Maybe it’s the ban on alcohol.” Tim was responding to Andy’s murmured comment on the eerie stillness.

“That, plus everybody’s resting up for tomorrow,” I suggested, reflecting on how serious the government took the possibility of election-related general strife. The ban on alcohol was a three day edict — covering the weekend plus the Monday aftermath of the polling — and a serious one. Not only was the sale of alcohol prohibited, but its imbibement also, even in the privacy of home.

Anyone caught in possession, under the influence, or even with a whiff on his breath would be summarily hoosgow-bound. In fact, and incredibly, during my shopping trip that afternoon I’d been refused the sale of a few cc’s of isopropyl, which I mix with vinegar as an eardrop prophylaxis. (Ironically, the pharmacist had cheerfully coughed up valiums and codeine-based painkillers, which taken in tandem would be enough to send me onto the streets howling for the bloody overthrow of everything in sight.)

“Whatev-ER zee rea-SON, eet is very quiet tonight,” Tremont said, as we paused on the stoop of a local eaterie.

“Yeah, it’s quiet all right,” Tim agreed, then mustered a feeble John Wayne imitation. “Too quiet.”

#

Very late night now and here’s one of the thoughts I’m having as the rain batters La Casita Viajera in oscillating white noise waves, like a rising oceanic groundswell rolling over the reef at The Point: a small band of Salvadorans in well-tailored but casual street clothes batters open my locked back door and with silenced Ingram Mac-10s adroitly dispatches my dog and me. One remains behind, quickly and efficiently cleaning up the blood with sponges and a special fluid developed for that purpose, while our bodies are wrapped in plastic sheets and stuffed into the trunk of the non- descript late model sedan with doctored plates that the men had arrived in. Ana Maria, the pretty young Salvadoran woman who owns the hotel, having seen from her bedroom window the shadowy figures emerging from the car in the driving inclemency of her courtyard, is still kneeling by the bed, eyes tight, rosaries clutched, as the vehicle turns down the street and evaporates into the night as if it had never existed.

Later, after the remains have been burned and buried in a fallow cane field just outside town, the leader of the right wing death squad visits a room in the back of the U.S. Embassy annex. As the door swings open, Erik puts down his crypto-secure sat phone and says, “Did you get the film?”

#

After our dinner in town tonight Shiner and I were approaching our niche in the hotel courtyard when I suddenly started feeling weird. I looked around: the street was completely deserted and dappled pools of water glistened in lustrous silver in the misty rain, like stepping stones of liquid mercury. The effulgent chiaroscuro of the street and shop lights was cinematic in its starkness, like the old Technicolor effect from 1940s musicals. But this was 1997 in El Salvador and Fred Astaire was no where in sight: I was more reminded of that part of a movie crafted to alert the audience that something bad was about to happen. Maybe it was the thunder and lightning, too — the ultimate ominous cliche — but whatever, I suddenly had the shakes.

It was here that thoughts of Erik first re-surfaced, treacherous and mean, along with vague inklings that I also had other things to worry about. Fuck, I was suddenly thinking, as if struck by a lightning bolt of clarity from the lowering sky over the town, if he were a spy, he’d done everything exactly as he should have — he’d persuaded me that without doubt he was clean as a hound’s tooth. Which of course told me nothing. His convincing manner might only have meant that he was a really good spy.

Hey, think about it, I was further thinking, what the fuck was I doing running around a country like El Salvador accusing people of being spies?

Was I nuts?

#

This was several hours ago. Between then and now (I’m still physically hunched and psychologically bent while the peaking tempest shakes my little house that travels), I’ve come to the conclusion that I do in fact have several things to worry about, here in La Libertad, El Salvador.

If Erik were in-country with clandestine and nefarious intent, hadn’t I with my big mouth and wise-ass photography compromised myself in the eyes of a covert and callous branch of my own government, and maybe the right wing powers-that-be of a brutal and cold-blooded, essentially renegade state?

And if the other side, the FMLN, were aware of Erik’s presence and unsympathetic intent, my relationship with him could easily be misconstrued as being one of a cohort rather than an accuser. What had German and the hardboiled former guerrillas at FMLN headquarters really thought of me? What sort of information did they already have about me?

And there was those little bits of business at the bank and with that Hispanic fellow (I’m not assuming he was Salvadoran) with the cryptic business card, who, having thought about it, didn’t really want me to know his Washington-based election-monitoring corporate connection.

Just who the fuck were these people and what were their affiliations and agendas?

One of the questions I’d asked Bob Rotherham was how he’d dealt with the obvious hazards of living in a country torn by violent internal strife. His response had been vehement and to the point: never get involved in, or give the appearance of getting involved in, the politics of the country.

Well, I hadn’t gotten actually involved in politics in El Salvador, but what appearance had I projected? My image of a rambling surfbum notwithstanding, and given my aforementioned movements and general nosy, vociferous behavior, I would appear to have been a busy and possibly bad boy, from the point of view of anyone — of any political persuasion — closely watching the activities of foreigners in La Libertad.

With a clamor of people and permutations milling about in the gray matter of my disheveled upstairs garret, I’ve just taken one of the valiums I scored today in town and as I wait for it to kick in I’m thinking of James Ortega (a fellow gringo and one who knew whence he spoke), way back at customs, and his wild-eyed admonition that I keep to myself in El Salvador, that I DON’T TELL ANYONE MY BUSINESS HERE. Well, I’d gone a bit beyond that, hadn’t I?

Yes, James, there is indeed a certain tension in this country, and I am feeling it tonight.

#

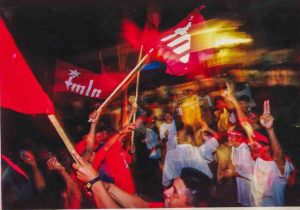

It’s somewhere around 10 P.M. on election night and I’m outside by the rig listening to the roaring din rising and falling from the barrio like the changing moods of a stadium full of rabid soccer fans. I can see the wavering flicker of fires that have been lit on the streets reflected on the crumbly side

There have been certain times in my life when I’ve risen above my fears, or at least put them temporarily aside, and, for whatever reason, done something blatantly ballsy, if not outright stupid. Tonight, it appears, is going to be one of those times. I’ve loaded up my camera with high speed print film, slid fresh batteries into my flash unit and packed various lenses and accessories into my lightweight tote bag for a little photojournalistic foray into the chaos of the streets.

Okay, fuck it, I’m thinking as Shiner and I wade into the rushing current of hyped up humanity flowing westward down the main drag of the barrio bajo and are swept downstream towards el centro, the heart of the town. Having the aspect of missionhood seems the safest demeanor – as opposed to, say, utter, abject, helpless terror — so I put on a determined face and fall in with the flood of fast movers, as if I know exactly where I’m going, am in a hurry to get there, and in no mood for any goddamn nonsense of the mugging or assault with a deadly weapon sort.

The crush of jostling Salvadorans intensifies as side alley tributaries feed the volume of flow but with the added pressure at once impede it. As we momentarily bottleneck I’m chagrined to notice that the Federal Police Station is locked up tight; indeed there is no sign of official presence on the streets, none of the usual burp gun-toting soldados lurking in sullen vigilance on corners or skulking in shadowy doorways. Great. Even this crazed, trigger-happy police state has decided to give up the streets tonight, such is the lunacy of the moment.

We finally get where we have no physical choice but to go, as the river’s inexorable flow terminates at a backed up, static pool of milling, edgy locals staring intently toward an old warehouse on the north side of the street, and who seem to be waiting for something. From their red head and arm bands and the crimson flags and banners being brandished, it’s obvious that the crowd is predominantly, if not exclusively, FMLN. Shiner and I jostle our way closer to the front, with me shouting “Perdon!” and “Lo siento!” — Excuse me, I’m sorry — when the mob erupts with a roar and upraised fists; I then see what the commotion is about and why the town has gathered in front of the warehouse — a large cardboard box is being carried out of the building by two men clad in FLMN colors; I catch the word “votaciones,” which I toke to mean “ballots,” hand lettered on its side: the vote is being tallied inside and the mob is awaiting the results.

The FMLN is the country’s left wing political party; former guerillas legitimatized by the 1992 ceasefire.

With the crowd cheering, chanting and waving flags as the ballot box is carried off, it’s an obvious photo op so I raise my camera over my head for an unobstructed angle and press the shutter, thinking Here goes. Sure enough, with the blinding pop of the flash heads everywhere turn and the cheering and chanting abate as I’m given a big time once-over. I grin inanely — sort of a Steve Martin coat-hanger-stuck-in-the-mouth effect (text missing)

I’m aware that the camera’s flash amounts to another neon arrow with a COME AND GET IT!, or, worse, HERE’S THE GRINGO TROUBLEMAKER YOU’VE BEEN LOOKING FOR! caption, but there’s nothing I can do about it, so I pucker up and fire away again. Fuck it.

It’s here that a couple things happen that turn my tenuous situation completely around. First, German materializes a couple rows back in the mob, grinning that big grin. Ignoring the dour stares of the people between us, I inquire over the din as to how the tally is going; he nods, his grin somehow widening still further. I give him a thumbs up, then point at his headband and ask where I can get one. He whips his off and tosses it to me. I don it and smile, this time genuinely, at the crowd around me, making eye contact with certain individuals, who, now that I’m wearing their colors, seem to soften.

Then I feel someone tugging at my sleeve — a tiny, wizened old woman clad in FMLN red and struggling with the weight of a large vessel of water. She gestures for me to have some. Although I’m thirsty, I only fake a sip, not wanting to imbibe Salvadoran tap water. She then bends over and pours a stream so Shiner can take a drink. For some reason, who knows why, this is what does it. As my dog laps and laps, a cheer rises from those around us, along with good natured laughter and applause.

Suddenly my presence is accepted completely, too completely, in a way: everybody wants to be photographed — they grin and mug when I point my camera at them, which kills the spontaneity of the images and softens the drama — although there is still a bit of genuine drama in the offing, and here it comes now, in the form of a cadre of electioneers in ARENA t-shirts filing up the street toward the warehouse.

Severely outnumbered ARENA delegates try to smile as they are intimidated by angry FMLN former guerrillas.

There is a truly ominous rumble from the FMLN multitudes, deep and unnerving, as representatives of their former tormentors approach in tight formation, to their credit keeping up the appearance of staid nonchalance in the face of a vast, angry mob.

Well, it’s close. As the FMLN ranks advance menacingly on the ARENA brigade, German and another, older man appear, moving swiftly around the perimeter of the interlopers, exhorting the crowd to cool down, to stay tranquilo — to my surprise and relief, the mob obeys and parts, letting the ARENA delegation enter the warehouse.

As the crowd mills, awaiting further developments, I catch another glimpse of German, by the warehouse door, maybe 20 meters away; he nods shortly but significantly to someone behind me and then seems to glance in my direction. Absent that big smile, his face seems older, harder. Not wanting to be obvious, I wait a moment then turn casually to see what that had been about. A young fellow I recognize as having been at FMLN headquarters the day before is a short distance away. I’d noticed him behind me earlier and suddenly I get a bad feeling, a resurgence of the fears I’d been wracked with of late. But then we make eye contact and his steady gaze and subtle nod tell me something else.

He’s there to watch my back.

I glance again at German, talking intently to an agitated FLMN partisan by the warehouse doorway. His youth and happy-go-lucky mien notwithstanding, German has turned out to be, after all, no lightweight. He’d stood up to and faced down an angry mob, and had the foresight to see to my well-being. He may have illusions about the wisdom of the American people, but he also knows, I suspect, that from a strictly political standpoint, my coming to grief in the midst of his people would certainly do his cause no good. No matter who I really am.

Now I’m suddenly thinking that he probably had fought in the war — how else to explain the respect and deference shown him by the older, combat-tested men of the FMLN? Barely into his teens near the end of the war, he’d maybe seen as much as some of them; maybe he’d participated in the storming of the government garrison at La Libertad — a fifteen year old freedom fighter ducking doorway to doorway, braving small arms fire in his effort to free his home town from a vicious totalitarian regime.

In any case, he’s revealed himself to be a very smart and courageous young man. And for whatever reason, he’s shown me kindness and concern; I will always remember him for that.

The ARENA delegation is now emerging from the warehouse carrying a ballot box and as the FMLN supporters fall into a reproachful silence, but making no move against them (again, German is right up front, ready to intervene in his former enemies’ behalf), I realize that at least three FMLN boxes had come out for ARENA’s one. If this is indeed the system — each party taking home the boxes with their votes after the count — it looks like it’ll be the FLMN by a landslide. (This is also obvious from the 100% FMLN composition of the street rally.) If, that is, there is no tampering with the final returns.

As the ARENA delegation disappear down the street, I notice the old woman with the water vessel nearby, standing alone. I want to know how many loved ones — sons and brothers and cousins and perhaps a husband — she’d lost so her people would have the right to vote, but I don’t have it in me to ask; so instead, I step over to her and say, “Es mejor que guerra, verdad?” Its better than war, right? She grabs my wrist and squeezes it tightly and I believe she has a lump in her throat also.

My friend and protector, German (HERR-man). If you’ve seen the terrific film Under Fire (with NickNolte): German reminded me of the kid who wanted to be a Big League pitcher, and was shot in the back by the Ed Harris character (who stole the film). In fact, from what I saw, felt and was told, El Salvador during La Revolucion was much like that movie. Reagan laid waste to much of Central America in the 1980s. (It was prose like this, I’m sure, that caused Men’s Journal to cancel publication of this story.)

#

Later, back in La Casita Viajera, I’m at the settee making notes about my experiences tonight. My thoughts wander first to my situation here, to just where I actually stand in all this. It’s obvious now, of course, that the FMLN bears me no ill, and with a rueful smirk I’m thinking no one else probably does either. A true dilettante after all, I’d cavalierly meddled for my own amusement in a situation the history and even current status of which I am abysmally ignorant. No, this was not smart, but in the end, who cared? My paranoia regarding the marshalling of evil forces against me had been largely a matter of ego, I wryly surmise, a way of inflating my own image of myself, like Erik’s reaction when I accused him of being a spy.

Ah, Erik… He’d no doubt just come down for a few days of relaxation at the beach and there he’d suddenly found himself, a key player in a plot to assassinate a homeless surfbum and his floppy-eared canine cohort. Poor guy.

But on the other hand, and here we go again… maybe, just maybe I’d been spared by the skin of my teeth after heated clandestine meetings of both sides: Erik and the right wing government operatives — the Hispanic guy with the business card and the cold-blooded bankers had lobbied passionately for my demise, but Erik’s cooler head had prevailed; and in the back room at FMLN election headquarters, German and his table pounding colleagues — choruses of “the yanqui must die!” overridden by German’s reasoned analysis of potential repercussions.

Erik and German as my saviors, mis salvadores?

Unlikey, but in this crazy country of El Salvador, who knows?

#

You fire up the rig right at first light and then rumble slowly down the deserted street where just a few hours ago the town of La Libertad had gathered to fervently participate in a democratic process you take completely for granted, and indeed, are cynically scornful of; a process that here had been earned at the cost of tens of thousands of lives and incalculable pain and suffering. As you pass the pockmarked, dilapidated warehouse on the left, you find yourself hoping that all went well with the final results, and that the declared winner, whoever it had been, had actually gotten the most votes. At the far end of town, just before the gas station at which you’d spent that first night, you come upon a parked bus with a man standing on the bumper, cleaning the windshield. You pull over and call out, “Sabe usted quien gano las elecciones?” — Did he know who won the election?

“Si,” the man says, smiling. “El FMLN.”

You nod and return his smile, then as you continue on up the street, you find yourself banging on the steering wheel with your fist, saying, “Great, that’s fucking great.”

#

As it turned out, ARENA stole the election.

Anyone who was there that night knows that FMLN won and won big. See my photos; it was like that everywhere. No doubt the CIA spooks had a hand in it; I have to wonder if Erik was indeed a part of it. I would bet yes. (Click the photo I took of him and notice how tense he is; his face and his body language, how tight his folded arms are.)

And I now know for sure why Men’s Journal didn’t run the piece. How would it look if they blew the whistle on a U.S.-backed stolen election?

53 comments for “Election Night in El Salvador”