Note: The author claims ‘Fair Use’ regarding the images and words that follow, given that this essay is a commentary on matters of culture, politics, dishonesty in media, the well-being of humanity, and possibly its very survival.

Dear Mr. Friedkin & Mr. Letts,

In the following essay I accuse you of what I consider heinous crimes, crimes against culture, honesty, that which is right and good, and humanity itself. The thing is, I have to do this. I’ve come to a point in my life wherein this sort of exposé is what I do. I am obsessed with recognizing and understanding profound untruths.

If I am wrong about anything I urge you to be in touch (allan at banditobooks.com), so I can correct the error(s), and if appropriate, apologize.

Although I am addressing my blog readers, what follows is directed at you.

Every seriously wrought story asks a question – which amounts to the storyteller’s promise – that will be answered by the ending. Meanwhile, all the machinations of plot and character, the story turns, must on some level be related to that question. Assuming this, in the movie Bug the question, at least as I see it, is this: Are Peter and then Agnes the victims of a continuing, horrific government experiment or are they delusional? (Another way to pose this: Are the ‘bugs’ real or ‘in their heads’?)

Addendum: Looking back after having finished this essay, I have come to see it in a similar way, with the question being this: To what extent does the concept of ‘delusion’ spill out of the screen and involve the audience? And to what extent are the storytellers (Friedkin/Letts) victims of their own brand of delusion? Or is it a profound and malevolent dishonesty? As we will see, the latter is surely the case.

Bug is in part a crafty discrediting of ‘conspiracy theories’, defined as anything that goes against what we are told to believe by the powers-that-be (PTB). And it’s more, much more, for what it represents, on several levels.

I spent a few hours looking into the history of Bug, interviews and bios and such, plus the reviews (mainstream plus Amazon and other audience analyses). I found the following from Wikipedia to be a typical example of how the critics, the audience (based on 573 Amazon customer reviews, which, including the ‘critics, I will refer to as ‘The Blind 600’), and indeed the storytellers themselves, interpreted the movie:

Bug is a 2006 psychological horror film directed by William Friedkin, and starring Ashley Judd, Michael Shannon, Lynn Collins, Brían F. O’Byrne, and Harry Connick Jr. The screenplay by Tracy Letts is based on his 1996 play of the same name in which a woman holed up in a rural Oklahoma motel becomes involved with a paranoid man who suffers from delusional parasitosis and is obsessed with conspiracy theories. [my emphasis]

The above ‘analysis’ is not only incorrect, but the diametrical opposite of what the story on the screen says and does (dialog and action). It not only gets the subtextual meaning dead wrong, but doesn’t seem to have registered the events depicted on screen. This appears to be denial on a level I haven’t seen before, evidenced in a piece of fiction, as opposed to media-induced ‘real life’ cognitive dissonance.

Not only is the answer to the first clause in the ‘story question’ a profound ‘No, the couple is not delusional,’ but the second question, ‘Are they the victims of a continuing, horrific government experiment’ is answered with a vehement ‘Yes!’

No one has noticed this reversal of truth. No one has noticed that no one has noticed.

Notwithstanding that what is happening (as the Bug story progresses) could not be more obvious, I found that in reading the six hundred (600) reviews, not one, not a single one, interpreted the story correctly… sorry that I have to repeat this… not one even understood what happens on the surface level (the action/dialog). I found this so astonishing that I ended up reading everything written about the movie I could find. It was all the same.

The fact that the storytellers themselves apparently do not have a clue as to what happens in their story, or what it means, led me to another dive down another rabbit hole.

Although the following story analysis is crafted with the assumption that the reader has viewed Bug, it is detailed enough that a viewing is not strictly necessary. But yes: Spoilers! (For the full effect of what I am going to say, to prove, a viewing before reading on is recommended.)

I’ll use screen shots from the movie (Fair Use!), with the more obvious observations in numbered image captions, and my observations in the adjacent text blocks. With certain story turns I will be ‘jumping ahead’ to what I know to be true via coming action, which can spoil ‘suspense’. This essay is not meant to entertain (it’s certainly not an alternative to a movie viewing), but to educate. Read the numbered captions first (click the images for a full page viewing).

BUG, A STORY BREAK-DOWN/ANALYSIS

1. A seedy rural Oklahoma motel, where Agnes (Ashley Judd) lives alone. Helicopter shots and sounds are a continuing meme.

We begin with a chopper shot (plus the sound thereof) that tells us we are out in the country, with a seedy motel our destination.

It’s here, tonight, that Agnes will meet Peter (Michael Shannon). This is a turning point that will change (and end) both their lives.

But for now they haven’t met. Before they do, the tone of the story is set…

2. Agnes gets repeated hang up phone calls and assumes it’s her violent, possessive, psychopathic ex, Goss, whom we learn has gotten out of prison early.

The idea of illicit, covert surveillance is all over the opening imagery, and anyone unfamiliar with the matter of Targeted Individuals (TI), i.e., electronic harassment, should take some time to look into it. ‘Do your research!’ (as Peter tells Agnes — in effect telling the audience — several times). Whether ‘TIs’ are real or not is not the point, given that Bug is fiction. The idea of it is very real, as is the predictable mainstream claim that it’s based on ‘delusions’.

From frame one, Bug builds on the notion that a deep and unseen cabal of the powers-that-be (PTB) may be constantly working behind (or beneath) the scene(s). As the evidence mounts, the notion becomes reality.

3. The next morning Agnes finds a flyer on her car windshield. She scans the motel lot: No other cars have flyers.

In context, this little bit of business is important: Along with the hang up calls, it implies that Agnes is under surveillance by an unseen, evil (maybe Evil) force. (It’s logical that the same entity who did the calls also left the flyer.) Or it could all be coincidence. Does anyone believe that? No, not in this story.

Addendum: One could have a field day analyzing the flyer’s content… for one, the words ‘Foreign and Domestic’ echo the U.S. Constitution, defining where enemies of freedom originate (in subtext saying we have to fight them). I guarantee not one word is ‘by accident.’ (What does ‘B&B’ mean?)

4 Agnes goes shopping and remembers how she lost her six-year old son, Lloyd, ten years previously. He ‘just disappeared’ from the grocery store, and cops (Feds/local) would not help her find him — which prompts us to wonder why they won’t help. (They are following orders from a much higher power.)

The events behind the disappearance of Agnes’s son will be an Act Three turning point that assures us that although Peter has been driven ‘frantic’ by the PTB, he is not delusionally insane. (That every reviewer — over 600 — ‘diagnosed’ Peter as delusional needs an explanation. )

As with the flyer (and of course the calls), none of the details and bits of business are superfluous in Bug.

Unfortunately, as we will see, the storytellers are either part of the powers-that-be (PTB) agenda they so craftily depict in their story, or are themselves victims of deep delusion. I am saying it’s the former.

5. Agnes works at a local sleaze bar with her buddy, RC, a lesbian. Lavoice (whom we never meet), RC’s lover, is in the midst of a legal custody battle over her kid, which will soon go to court. RC is worried.

This scene about Lavoice’s custody issue is the first of a total of four story-beats on this subplot.

The later resolution of the issue will re-enforce the point that unseen evil powers are manipulating everyone. (Again, the alternative is that everything is a coincidence, which is unlikely in a story of this depth; it would also be boring, i.e., bad storytelling.)

6. RC brings a lone drifter, Peter, to Agnes’s motel. At first Peter comes across a bit eccentric, although quiet and probably harmless.

As it will turn out, RC was persuaded to introduce Peter and Agnes in return for a promise to settle the custody battle in Lavoice’s favor. (Letts often plays with names, ‘Lavoice’ [‘the voice’] being a subtle way of saying ‘Listen!’)

This again tells us that the invisible PTB can fix anything, do anything. It is God-like in its influence.

As Peter will figure out, his meeting Agnes ‘is no accident.’ Repeat: Their very meeting was pre-arranged by outside forces, represented by the on-screen personage of ‘Doctor Sweet’.

Addendum: If it appears I’m making assumptions based on little evidence, I assure the reader that I am merely jumping ahead to clearly stated or implied revelations and action to come.

7. RC exits, leaving Agnes and Peter alone. Their relationship blooms, tentatively, with Agnes offering Peter her couch for the night.

This ‘getting to know each other’ sequence is rich in subtext and set ups. Peter claims to be a bit psychic and indeed senses that Agnes has a child, although she had denied it. (He also says, ‘You’re lonely, that’s for sure.’) Agnes tells the story of her son Lloyd’s disappearance…. The two search for a ‘cricket’ and Peter finds it in the smoke alarm and kills it (although it’s a set up, this first ‘bug’ reference is innocent, a part of their ‘foreplay’)… Peter seems to ‘know’ things about how the world works, but it’s unclear at this point if he is… unhinged or not.

As we will see: Although some of his ‘theories’ are off the mark (but not too far), Peter is far from insane. Part of this exercise is to explain how/why, in the 600-plus reviews and critiques I studied, not one of them understood even the surface story-line. Again — this is worth repeating — none even understood that the main question the story asks is the following: Are Peter and then Agnes the victims of a horrendous conspiracy or are they delusional?

This is a question to be answered, not a premise.

Again: As I found in my research, it is not only the mainstream and alt medias that get the story completely wrong, but the audience as well. We will return to this subject after this story analysis proves beyond doubt that Agnes and Peter are actually heroic characters who sacrifice themselves trying ‘to save the world.’ This is the polar opposite of every interpretation I have come across, and I have searched high and low.

And it’s worth repeating that it gets worse: Friedkin/Letts, the storytellers, are either delusional themselves or part of a mind control agenda that is rife in the entertainment system. (The other possibility, of course, is that I myself am delusional. I leave it to the reader to decide.)

But continuing on with the story… the morning after Peter innocently spends the night…

8. Agnes awakens to a scary surprise. Peter is gone and Goss, her ex, is helping himself to a shower. Goss has unexpectedly been released from prison and seems to assume Agnes will welcome him. The scene is cat-and-mouse he said/she said, Goss bragging that he has some ‘bigger fish to fry’ when it’s obvious Agnes wants nothing to do with him.

From the get-go Goss’s behavior makes no (surface) sense: He comes ‘home’ from a two-year armed robbery stretch to find that Agnes (whom he feels he owns) spent the previous night with some lame drifter (he saw Peter leave) and doesn’t seem to care (not about sex); nor is he interested in having sex with Agnes; this after two years of forced fem-celebacy in the pen. Does this make sense?

What makes sense — and this will apply to all of Goss’s behavior — is that he is a part of the PTB conspiracy and is there to spy on Agnes/Peter and to influence them if he can. (Inarguable proof of this comes when Goss leads Doctor Sweet to the motel.)

It is no coincidence that Goss arrives at the same time as Peter. In fact, there are no coincidences in this well-wrought tale of mind control and the courage it takes to fight back.

9. Agnes asks Goss if he had ratted out a mutual friend because the friend flirted with her. Friedkin goes to close up for Goss’s answer: ‘Yeah.’ Yet he’s not outraged over Peter. The viewer should be wondering about this. (As we’ll see, nothing that points to a ‘conspiracy’ will be remembered by the audience; 600 ‘forgetful’ reviews indicate this.)

Goss somehow got out of prison early. This is hinted at in dialog but is obvious from Agnes’s surprise that he did get out. In her position, given her fear of her violent, jealous, psychopathic ex, she would have kept track of exactly when he would be turned loose.

Goss’s release is important because it needs an explanation, and the only one is that the PTB (via Doctor Sweet), arranged for for it, so Goss could do some work on Sweet’s ‘The Peter/Agnes Project.’

10. During their he said/she said Goss denies he was behind the hang up calls, and he is believable. (Indeed, why should he do that?) This re-enforces the idea that Agnes is under surveillance from an unknown power (as does the ‘flyer’ business). Goss is moved to violence when Agnes mentions their ‘disappeared’ son, Lloyd.

The subject of their son Lloyd and how he disappeared is vital to the story. Goss’s violent reaction to Agnes’s mention of Lloyd and his (Goss’s) vehemently blaming her sets up later events which will finger Goss as having sold their son to the PTB (again, through Doctor Sweet), to use in their MK-ULTRA-type projects. (Research indicates that MK-ULTRA-type experiments are often multi-generational.)

After Goss slaps Agnes he picks up a shirt that belonged to the son, sniffs it and murmurs, ‘Little shit.’

As I say, there are no red herrings, no throw-aways, in this well-crafted story. That Goss would voice contempt for his missing son says a lot about what he is capable of; even the sniffing of the kid’s shirt will turn out to be significant for how it subtly refers to biology,…’to flesh, to DNA’ as Agnes will later realize.

11. Peter enters and although Goss makes fun of him, he doesn’t react with the violence we would expect, given his temper and possessiveness toward Agnes.

If Goss is so crazed with sexual jealousy/suspicion that he would rat out a buddy to the law for a flirtation, then why does he treat Peter with such kid gloves?

The only answer — and it fits with everything else — is that Goss’s ‘bigger fish to fry’ entails a mission to spy on and manipulate Agnes and Peter, in return for his early release. As we will see later when Doctor Sweet appears, this is the only explanation for Goss’s behavior.

12. Goss leaves, saying he will return. Peter warns Agnes about how dangerous the world is, how people will try to control you, make you crazy even. Agnes tells Peter about her son, Lloyd, and his disappearance.

Peter warns Agnes that they can never be safe on this planet, not with ‘all the technology, and the chemicals, and information.’

Reminiscent of a scene from Cuckoo’s Nest, Peter tells Agnes that ‘The machines… people working the machines, their works, humming,’ are a threat and that ‘Nothing makes them happier than knowing people are aware the machines are up and running.’

Although this sounds a bit unhinged, it conflates with the hang up calls, the flyer, and Friedkin’s machine imagery, i.e., the ceiling fan, the air conditioner humming, and so forth.

In the play and movie both, we often faintly hear the sound of a helicopter, which fits with the notion of surveillance, machinery, and an unseen threat. Whether or not the unseen chopper is real (or sometimes is real, sometimes not) is one of the few questions not outright answered. Having said that: If one pays even minimal attention, it’s obvious what’s going on in this story.

Addendum: I was so astounded by the misbegotten reactions to Bug that I saw fit to archive a slew of typical ones. Some will appear in the text below but I think it important that the reader actual sees the… the body of evidence, so I pasted in a lot more at the end of this essay. I strongly suggest that at times the reader take a break from my analysis and at least scan what ‘the world’ believes about this story. (That there are no exceptions out of 600 indicates that it really is the world’s take on the story.)

Back in the story, Peter and Agnes have sex… or should I say, ‘Peter and Agnes mate.’

13. Agnes warms to Peter, telling him he can stay another night. Peter says that although he hasn’t had sex in a long time, he could do it with Agnes, who replies ‘Come here, boy’.

Although this image is not very sharp, I’ve chosen it because of the subtext. Here Friedkin accentuates the ‘exchanging of bodily fluids’ that is inevitable with the sex act. (Here they ‘swap spit.’)

The rest of the imagery is abstract and not particularly ‘sexy’ or intimate; aside from this image he rarely puts the lovers in the same frame.

He is telling us that this sex act is about biology.

14. Intercut with the sex imagery we see flowing blood and… bugs… This is the last image in the scene. It’s so brief (four or five frames) that you could blink and miss it.

This brief and shocking image comes at the climax (literal and figurative) of the sex scene, and in the sense of film logic answers the story’s defining question in this manner: The bugs are real.

Every image in a movie has a point of view: it could be a character’s, i.e., we see what the character sees or imagines or hallucinates. Otherwise, the image is ‘real,’ meaning in the reality of the story. Has to be one or the other. So if neither Peter nor Agnes is ‘imagining’ this visual, then the bugs are real.

Think about this. So far in the story no one has mentioned bugs or seen bugs, and aside from the cricket (which was a thematic set up and a bit of business for Peter and Agnes to do while getting to know each other), we haven’t heard any bugs. The first time the notion of bugs comes up is at least a day/night after the sex scene (maybe a week, we don’t know), when Peter wakes up from a bug bite, after which there is an emotional scene wherein Peter tells his horrendous backstory, i.e., the experimentation done on him at the secret military hospital (at Groom Lake, which is a.k.a Area 51). Even then, after the first incident with the bug bite, no one mentions bugs. (Every one of the ‘analyses’ I’ve read somehow misses this important point.)

So there is no ‘character logic’ that would have either of them thinking or hallucinating the image of a bug during or at the climax of their sex act.

Addendum: To go even further, if one of them (especially Agnes) had ‘imagined’ the embedded image above during the sex, he/she surely would have mentioned it during their rants at the end of the film, when they referred to the sex and how it ‘bred’ the bugs: ‘Hey, when we had sex I imagined bugs! A big green mother bug!!’ Or ‘After we had sex I had a nightmare about bugs!’ Nothing like this happened.

So as a filmmaker, with the above image Friedkin is giving the game away, answering the question posed by the premise, yelling in our faces that THE BUGS ARE REAL!’

Yet when Friedkin writes or talks about the movie he tells us something else altogether. This is from an interview specifically about Bug, and I’ll leave the paragraph intact to see if you pick up on ‘the problem’:

Friedkin: What attracts people to art in any form? There are a number of dark works that are intriguing because they reveal the constant struggle of good and evil that exists in all of us. I’m not just talking about where a guy takes a chainsaw and cuts somebody up for two hours and then the movie’s over. What you refer to as the dark side, I refer to as if it does have validity underneath the surface, it’s something that’s dealing with the thin line between good and evil that is in all of us. The character who seems to be the darkest at first, her ex-husband, is the guy that’s trying to save her. A lot of people don’t think about that aspect of it, but that’s what attracted me to this, aside from the great writing and the good roles.

If your mouth isn’t hanging open with your eyes narrowed — or if you have your own way of registering astonishment — if that isn’t happening right now… well, I’m not sure why you’re still reading…

‘The character who seems to be the darkest at first, her ex-husband, is the guy that’s trying to save her. A lot of people don’t think about that aspect of it…’

The easiest way to put it: I actually did read over 600 reviews/commentaries on Bug and can honestly say that Friedkin’s take on Goss and his part in the story is the…. the outright stupidest. Or to be kind… the outright most off-base. This is from the Academy Award-winning director of The French Connection and The Exorcist, and… Bug.

Addendum: It’s interesting, what’s going on right at this minute. After working for four hours on this story analysis, I got tired and lay down to read Friedkin’s memoir, The Friedkin Connection, which I bought on Kindle yesterday and of which I read a few pages last night. I’m looking for signs of… of who Friedkin really is. Signs of… guilt.

And I already found one, a sign of guilt. In ‘thumbing’ through the Kindle text I found a passage wherein Friedkin mentions Doctor Louis ‘Jolly’ West, a name that has come up several times in my research on how the world really works (HTWRW). Here’s what Wikipedia — well known as under the control of the PTB, an outright psy op even — says about Jolly West:

West was deeply involved in Korean War-era CIA brainwashing experiments, the Agency’s notorious[1] MK-Ultra mind-control program, and the use and intentional abuse of LSD (as it being administered to unwitting people, who then suffered traumatic hallucinations) – even at one point killing an elephant with it. [Yes, West is well-known as the ‘scientist’ who killed an elephant with a gargantuan dose of LSD. He said he did it ‘To see what would happen.’]

And the above is a chunk of West’s cv after the spooks had gotten to it and ‘cleaned it up.’ Point being that Friedkin had a close personal relationship with a full-blown MK-ULTRA monster. He is right out of one of Peter’s ‘conspiracy’ rants. And he’s Friedkin’s pal.

Now, today as I write, I realize that what I’m doing with this essay is to call out this famous director on profound dishonesty, professional and moral, and participation in an evil agenda. I strongly believe that Friedkin is heavily involved in the worst of the PTB/H-wood sins against truth and humanity. He is a ‘lifetime actor’, a deep cover mind-controlling sonofabitch. (Ditto Tracy Letts, who was probably lured in via honey pot career promises.)

There is a mind control agenda in the entertainment business, the movie business, and the Friedkin/Letts movie Bug — as powerful and superbly crafted as it is — is a supreme example of how that agenda works now, in present day. (I was heavily involved in ‘the biz’ for the decade of the 1980s.)

In case you’re curious about the other half of the storytelling team, here’s a bit of wisdom from an interview Tracy Letts did about the movie:

Tracy Letts, playwright, “Bug”: In the mid ‘90s, when I wrote this, it was partly inspired by the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, and an interest in what had drawn this person through conspiracy theory into this very dark place that he committed this horrible act. [I assume he’s referring to Tim McVeigh, which means he buys the official story.] And so, at the time when I started writing the piece in the mid ‘90s the internet was new to us as consumers. The internet was new, and of course one of the first things that flourished in the internet was conspiracy theory. Unfortunately, it’s just become, in the 25 years since I wrote the play, more and more ubiquitous and mainstream. Not the internet, conspiracy theory. It has really become mainstream. It’s part of our political discourse and yeah, it’s in the White House. We actually hear conspiracy theory reflected back to us from the president. [It’s of course my emphases; this repetition of the CIA-created term amounts to NLP, i.e., linguistic mind control.]

The above is either linguistic mind control or it’s the sort of dumb-ass ramble you might get from a low-level government troll or useful idiot. It’s someone hiding the truth.

Addendum: Letts brings up the Murrah Building bombing? And McVeigh? Anyone who digs a half inch below the ‘official story’ has to know that it was a false flag event, with McVeigh almost certainly either a mind-controlled patsy or knowing participant who went poof! and disappeared rather than be executed. Look into it.

There is something very wrong here, on a level that goes way beyond one movie.

But back to what happens…

15. Peter wakes up from a painful bug bite, which he shows Agnes. They go on a bug hunt to rid the bed of them, and Peter suspects an infestation.

It is at least a day/night after their sex that the ‘bugs arrive.’ Up until now, there has been no mention or allusion to bugs (aside from a cricket). Peter voices the idea that the bug might have been ‘matriarchal’ and carrying eggs. With reasonable logic he says if there’s one there is likely more.

Peter has a monolog wherein he says everyone needs a ‘center,’ a sacred place that is his alone. The antithesis of police state surveillance/control.

The phone rings. Static. Not Goss, Peter says. It’s significant that this happens as Peter is voicing his opposition to the PTB via the need for privacy.

We recall Peter saying: ‘They want you to know the machines are humming.’ Via this hang up call, the unseen power is telling them it is listening and reacting to everything they do. The evidence that they are being ‘targeted’ mounts.

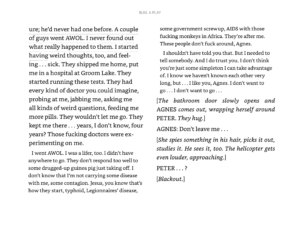

16. Peter spills his guts about his past as a victim of an MKULTRA-type medical experiment, after which he breaks down in desperation/angst.

But an argument erupts when Agnes demands to know Peter’s backstory and Peter bolts out, apparently abandoning her… but he returns and bares all about what was done to him in the military hospital (at Groom Lake, a.k.a. Area 51).

Peter’s confessional is important enough that it should be taken in in full, so I’ve embedded the relevant pages from the play (the movie is the same).

19. Peter’s allegation that some diseases (Legionnaires and especially AIDS) are a result of government screwups is, if anything, naive — they were more black ops than errors. ‘Do your research.’

It’s significant that at no time in Peter’s monolog does he allege that bugs were planted in his blood. Many reviewers (and even the storytellers!) imply that Peter claims he was experimented on and bugs put into his blood as if the bugs were part of his backstory. In fact, the bugs only appear after Peter is bitten (the night of the above scene).

The above emotional scene ends with Peter and Agnes united… against whatever comes next. And it comes quickly…

20. At the end of the above scene Agnes notices something in Peter’s hair, picks it off and shows it to him. A bug? Surely.

Notice that it’s Agnes who notices the bug in Peter’s hair. The impression you get from reviewers (et al.) is that Peter, either malevolently or innocently, spreads his delusional insanity to Agnes, who, they claim, is weak and vulnerable and easily beguiled, when in fact the opposite is the case: She only completely accepts Peter’s ‘conspiracy theories’ after inarguable evidence mounts up.

Put aside how the two are ‘driven frantic’ by unseen forces, and examine what they actually do.

These are heroic characters battling an ultimate force of evil, not a pair of weaklings on a drug binge that drives them to a horrendous mutual self-destruction. (In fact, Peter never even has a drink, let alone do drugs.) And seriously, which of these two stories is more interesting? Which story would, say, Oscar-winner William Friedkin be more likely to be attracted to? Mmmm? Then why is he representing the story of Bug as of drugged out weaklings?

21. As the lovers embrace and promise to stay together, the room suddenly shakes from an attacking heliopter.

This shocking ending to the above scene is obviously meant to tell us that Peter and Agnes’s vow will be under violent assault by the unseen force that has been following them and controlling them since… we don’t yet know how long they have been the subjects of surveillance and experimentation.

The storytellers are coy about the helicopter, i.e., whether it is real or in the minds of Agnes and Peter, and, as I say, this is the only issue that is not made crystal clear by the events themselves.

Fade to a new scene, time has passed. Peter is alone in the room, peering into a little microscope (Agnes’s son Lloyd’s, as it turns out) when Goss barges in. Goss has no stated motive for being there; he is in fact there to spy on Peter and Agnes: he registers the bug-killing chemicals and hanging bug traps and grills Peter. Again, ‘a mission’ is the explanation for his only playful hostility toward Peter. He’s under orders, as in finding out what Peter is doing… he elbows his way to look into the microscope, asking what it is he’s looking at. Peter explains that bugs are in his blood, feeding off him.

23. Goss is obviously holding back; he wants to beat the shit out of Peter… why doesn’t he? He is under orders from Doctor Sweet.

Agnes and RC enter and Goss tells a seemingly irrelevant story about how Lavoice, RC’s lover, ‘took a shit on a cop car from a balcony.’

This is another beat in the off-screen subplot of Lavoice’s legal custody battle. It tells us how unlikely it would be for an Oklahoma judge to award custody to a nutso lesbian like RC’s mate.

Later, when custody is won, we (should) know it was via the machinations of the all powerful PTB (Doctor Sweet).

24. Agnes demands that Goss leave, which he does without conflict (also against his nature). Now it’s Agnes, Peter, and RC.

Peter, at the microscope, urgently needs Agnes to look at the bugs he found in his blood. Agnes agrees about the bugs and even finds one burrowed in her arm. RC says she can’t see it. (This, I believe, is to plant some doubt in an otherwise obvious tale of two ‘little people’ battling the all powerful PTB. It’s ‘obvious’ yet no one sees this.)

Conflict arises when Agnes says she talked to the motel guy about the infestation and Peter erupts, saying Agnes ‘Doesn’t know what we’re dealing with,’ meaning the PTB and Doctor Sweet.

Agnes then admits she saw a doctor, who didn’t believe her about the bugs. (This is a typical mainstream medical reaction to Morgellons Disease, about which more to come.)

It’s in this scene that Peter starts to get… frantic… about the unseen power that tortured him for years with medical experiments. Is Peter’s behavior paranoia or due diligence for a man in his position? This question is never asked by reviewers et al. It is assumed that Peter is delusional and insane, notwithstanding the mounting evidence that he is up against an all-powerful, evil adversary.

In the midst of the argument, Agnes says she has good news: Lavoice, RC’s mate, got custody! Agnes says she just can’t believe it, not in Oklahoma.

Any thinking viewer (those with ‘eyes to see’, etc.) will now know that Doctor Sweet had a deal with RC: Introduce Peter to Agnes and the custody battle would be taken care of. (To doubters: What else is this subplot doing here? Huh?)

26. In this scene RC in effect admits to conspiring (with Doctor Sweet) against Agnes/Peter in return for help with the custody issue.

The conflict heightens when RC says she is taking Agnes away, to stay with her. As a threat she tells Peter about the man asking questions about him: Doctor Sweet. ‘Groom Lake,’ Peter responds. One of his torturers.

It is at this point — with the mentioning of Doctor Sweet (whose very name is a sly ‘tell’, since bugs are attracted to sugar) — anyone paying attention should now know that Peter’s ‘insane’ claims are true, at least basically. But this is a ‘slow reveal’, with much more to come.

27. Peter is ravaged with sores, but are they a product of delusion? The central question of the story looms.

Peter shows RC the ravages of the bugs, but RC echoes the dermatologist, who diagnosed ‘delusional parasitosis.’ (The same claim the PTB make in real life about Morgellons – which may be an artificial life form engineered by MK-ULTRA — the symptoms of which are the same as Peter’s.)

For those who ‘do their research,’ this story is starting to have ominous real-life overtones.

Suddenly Peter has a fit, as if the bugs are attacking him. Agnes frantically tries to help, meanwhile throwing Agnes out.

Addendum: The above mention of Morgellon’s Disease is not meant to distract the reader from what is going on in Bug, i.e., if the reader has not heard of it or doesn’t believe in it, do not use that as an excuse to go into denial about Bug. That Peter’s ‘conspiracy theory’ is in fact real is proved by multiple events in the story, especially the upcoming entrance of Doctor Sweet. Morgellons is very much a separate issue.

28. In a horrendous scene Peter pulls his own tooth with a pliers to get at the ‘egg sac’ planted in a filling.

It’s in this scene that the audience (et al.) is given the excuse, the ‘permission’, to believe that Peter is insane, no matter ‘the facts’, i.e. the multiple lines of evidence that he is in fact the subject of a ghastly government experiment.

The frantic and frightening delivery of the dialog distracts from the truth of the story; but this does not explain how/why everyone (the audience) slips into denial about what really happens in Bug.

29. During and after the tooth-pulling Agnes tries to rationalize Peter’s claims of PTB torture/harassment by saying ‘The Army wouldn’t do that to you!’ The most naive of viewers should smirk at this notion…

Agnes is starting to see the logic in Peter’s claims, notwithstanding his frantic delivery, plus of course the gory tooth-pulling itself.

Peter’s crazed behavior allows the audience to ignore (be in denial about) Peter’s list of atrocities the PTB/military has perpetrated, not only upon him but on us.

This is a form of mind control aimed at the audience itself.

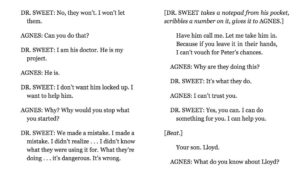

30. With the room now ‘armed’ against the bugs (with the classic tinfoil loonies wear as hats), there is a knock on the door. As we careen into Act 3 we are about to be TOLD the awful truth about what has really been happening to Peter and Agnes.

What can one say about the appearance of Doctor Sweet? And the fact that he is brought to Agnes by Goss, who breaks down the door for his boss, i.e., Sweet, the spook who got him out of jail early. How could everyone (critics, ‘The Blind 600’, the storytellers) not understand this?

My primary interest from here on is the process by which every critic can ‘deny’ what Doctor Sweet’s very appearance means, let alone an analysis of his behavior and what he reveals in dialog. And out of the 600 ‘civilian’ reviews, I believe only four refer to him directly, and in the same way Friedkin himself does (see below): one hurried line that avoided saying anything.

Addendum: If the PTB can ‘erase events’ from our minds regarding a piece of fiction, think what they can do in eliciting what Orwell called ‘doublethink’ about real life events, the best recent historical example being 9/11 [writing from 2022, I would bring up the ‘COVID psyop’] . Am I getting anything across?

31. The appearance of Doctor Sweet (again, that name!) with Goss pretty much says it all regarding our question.

I’m tempted to reproduce the whole Agnes/Doctor Sweet scene, for it surely contains the most important revelations in the entire story, but…

…but the real point to be made is in the dialog embedded below, starting with ‘We made a mistake…’

Whether he is lying, Sweet’s reveal on this page defines the story to be about two heroic characters battling the incarnation of evil.

Even if Sweet is lying about everything, the question of why he would lie about everything itself answers the question we all want to know the definitive answer to: Are Peter and Agnes delusional or are they in fact courageous fighters against the evil machinations of the powers-that-be?

Addendum: In my recent reading of Friedkin’s memoir, I skipped ahead to his description of the making of Bug. I was particularly interested in his views on the story itself: He goes to great lengths in describing his other movies, everything from who worked on them, who didn’t work on them, to his detailed analysis of the screenplays; you name it, Friedkin has a lot to say about it.

But when it came to Bug, the great director had almost nothing to say about the story, other than to echo most of the Amazon reviews, i.e., Peter is a delusional nutcase who sucks the lonely, vulnerable Agnes into his personal hell. Unlike most of the other 600 analyses I read, though, he does manage to mention Doctor Sweet:

‘A man claiming to be someone named Doctor Sweet, Peter’s personal physician, pays an unexpected visit, leading to murder and self-immolation.’

Wow. Methinks this Oscar-winning filmmaker might have missed something in his own story.

Please understand that this exercise is not story analysis ‘rocket science’. As I’ve shown, it’s all made very clear in action and dialog.

The real point of this essay having been made, I am tempted wind up this story analysis here, but the ending is so powerful and so moving that I feel I have to at least touch upon it.

Here, Doctor Sweet is about to lower the leverage boom on Agnes by bringing up her lost son, and what he can do for her…

I held back one detail, one more reveal, in the Agnes/Doctor Sweet scene. As a final lever to get Agnes to cooperate, Sweet offers to help her find her son, Lloyd, ten years missing.What? How could Sweet know about her son? Answer: It was Sweet who paid Goss to give Lloyd up to the MKULTRA ‘Project.’

This truly is the coup de grace for any theory that includes ‘delusion’ in its description of Peter and Agnes’s behavior. So if any of ‘The Blind 600’ are reading this: Do you understand now what was done to you?

But now back to the story, as Peter enters, not looking at all… healthy.

Here, Peter is about to kill Doctor Sweet with a butcher knife in retaliation for the years of torture Peter endured.

Peter kills his Doctor in a crazed rage, then refers to him as ‘a robot,’ with ‘synthetic blood’, and which ‘only says what it’s programmed to say’, so good riddance, and so forth.

Proof Peter is nuts, huh? How far off is he, really, with the ‘robot’ label? And anyway, if Peter is unhinged now, how did he get that way?

You tell me.

THE ENDING

‘Endings are everything.’

William Goldman, from Adventures in the Screen Trade

Having doused themselves with gasoline and declared their mutual love, this is the moment before their sacrificial death.

As with many a decent thriller or mystery, at the end of Bug the heroes (and they are just that) put all the pieces together, connect all the dots… sew up any story-holes or logic problems that might remain.

In a sense this is done perfectly in Bug, but on another level, the level of line delivery, the ending contradicts itself by inferring that Peter/Agnes are insane. (Not to mention all that tinfoil, symbolic of nutcases.)

Not that I would have had the actors do it differently. God, no. They are brilliant as two ‘Targeted Individuals’, the victims of of a depraved, bio-engineered travesty, meant to increase the PTB’s surveillance and mind control capabilities, at the expense of all humanity. At the expense of planet Earth.

I’ll not repeat all their dot-connecting here — delivered in a frantic, sustained bout of raging insight — but suffice to say that Peter’s deepest epiphany, his ‘I don’t believe I’m here by accident’ revelation — meaning that their meeting (and ‘mating’) was a planned aspect of ‘The Experiment’ — followed by Agnes’s insight that it was Lloyd’s DNA that matched hers with Peter’s (recall Goss sniffing Lloyd’s shirt)… this all brings us back to the opening scenes, and anyone with half a wit should themselves be having a profound ah-ha! experience.

During final credits two images flash on the screen, as if to remind us what Bug is really about. First this one of Lloyd’s shirt (that Goss sniffed), defining the (DNA) connection that linked Peter and Agnes. Absent this link, there would be no story.

If I were Letts/Friedkin (mainly Letts, the writer), for me the ultimate ‘audience’ would be someone who believed Peter was nuts and dragged the weakling Agnes into his psychotic state, but then… but now, with Doctor’s Sweet’s entrance and with these rapid fire reveals, finds him/herself crying out, ‘My God, they are heroes! How could I not have seen this?!’

This is an example of a perfect ending, wherein you don’t see it coming at all, but in retrospect, when you play back events in your mind, you see that everything was leading to this.

Addendum: Do I believe that out of the several million who took in Bug, there is even one such audience member? Truthfully, no. Not one. Go to the Amazon Reviews… read it and weep. Chalk up a major victory for the PTB.

The final image, which confused one reviewer, who wrote: ‘Why was there an image of a dead man at the end?’ A dead man? It’s Doctor Sweet, you fucking moron, to remind us who represents the antagonist, i.e., the Powers-That-Be.

Yes, and this example of brilliance in storytelling was called lunacy and ‘delusional parasitosis’ by the world, the critics and ‘civilian’ reviewers and… ultimately the storytellers.

The new question: Why would the storytellers not want the world to know how profound and heroic this tale really is?

More to come on our new question, in Part Two of this analysis [which I never wrote…]

Addendum: One last thought on why I label Peter and Agnes as ‘heroic.’

Does Peter and Agnes’s self-immolation sacrifice to wipe out the bio-engineered, tracking-control transmitting bugs have any real-life precedents?

For me, being old enough to well remember that evil war we call Vietnam, what comes to mind is the Buddhist monk who doused himself with gasoline and set himself aflame on the streets of Saigon, to protest the war. Anyone grown up and sentient at that time will likely recall this horrendous event, recorded on film for the front pages and TV for the nightly news.

Did he stop the war? No, but he sure as hell gave it (the war) pause. Was he insane? Not in this sense: What more could he (or any one person) have done to… save the world?

Saigon, June, 1963. If Friedkin did a story about this man’s life, would he portray him as simply insane?

You see where I’m going with this, don’t you? Peter and Agnes’s fiery self-sacrifice will no doubt not save the world from the coming plague (of bugs); the evildoers will certainly have back ups in their underground Groom Lake lab. But that’s not the point, is it, in this personal story?

A sum-up reminder: Bug is mind control predictive (or pre-emptive) programming in disguise (as a psychological horror tale); it’s also important, urgently so, given current events, for how it discredits anyone who doesn’t accept the ‘official story’ about… say, the COVID-19 ‘virus’ (or ‘bug,’ in the medical vernacular) that is said to be ravishing the planet as I write. [For the truth about the COVID fraud, go here.] That the ‘bugs’ (in the movie), as self-replicating, transmitting ‘chips, prefigure the urgent (for the PTB) 5G rollout, should occur to even a neophyte critical thinker.

I’d much appreciate your spreading this Open Letter around the Internet, to the alt media (and for laughs the mainstream too) and whatever social media platforms you think might understand it.

Although I’ll never hear from them, if this goes viral, Friedkin and Letts are likely to get wind of it. If nothing else, I’d like them to know that someone is aware of what they’ve done.

Sort of the converse of ‘They want you to know that the machine is up and humming.’

Allan

Addendum: To go far out on a speculation limb… that Friedkin is now 84 but could pass for 60 is a prompt to wonder if he has the same ‘dermatologist’ as, say, Madonna or Marina Abramovic. Just sayin’.

My main interest isn’t in Friedkin or Letts or the moronic double-thinking critics (who are useful idiots and don’t have to be bought). No, my main interest and concern is still the matter that inspired me to do this analysis: Those I have referred to as ‘The Blind 600.’ If it were 90%, or even 98% that somehow ‘didn’t see’ the truth of Bug, I wouldn’t be as… obsessed… as I am. It’s that 100% stat that has me outright frightened.

How did this happen? And on the broader scale, and to use a comparison that only seems ridiculous, how did the cultural image of the American family go from Father Knows Best to Killer Joe?

Killer Joe. I do recommend that the reader take in this other Friedkin/Letts collaboration, which I will touch on in Part Two as another example of the sort of ‘culture creation’ that also gave us the ‘Love Generation’ of the 1960s – 70s (which I was very much a part of).

Oh, do you think that the era of the hippies and the drug culture and the aforementioned transition to Killer Joe was ‘accidental’? Or ‘a natural evolution’? As in Bug, nothing is a ‘coincidence.’

And for newcomers to this forum here are my two favorites of the films I’ve made on my own. Water Time; A Road Interpretation of How the World Really Works, and this ‘Orwellian’ interview about the sort of denial we’ve been dealing with.

END NOTES (Evidence that no one understood Bug, even on the level of simple plot/action/dialog)

These ‘reviews’ (both ‘professional and ‘civilian’) are In no particular order (with the exception of the first one).

It’s true. Parasites play a huge role in the way things work in this world. Our government is controlled by parasites with a hive mind that are connected to entities on another plane that are transferred from one individual to another during sex rituals. Research it for yourself. If you ever wondered why politicians don’t seem quite human, it’s because they aren’t. People call them parasites without realizing how right they are. This movie barely scratches the surface of just how bad it is. [I know: He’s nuts but at least he’s headed in the right direction]

The movie becomes even more ridiculous when in the end the writer attempts to mix in actual documented government experiments (uncovered by the U.S. Church Senate committee that were conducted on innocent civilians during the second half of the 20th century) and other documents released under the freedom of information Act with fantasy conspiracy theories one might expect from mental patients with real brain disorders.

I have worked in healthcare for 20 plus years and have worked with many people patients or otherwise with very altered versions of what most perceive as reality. I applaud the performances but the plot doesn’t draw me into to believing this is a possible story line, probably because my education and experience hold me back.

It is a horrifying tale of paranoia, and how contagious it can be.

Just before Peter kills him, we see that Doc Sweet was about to do him harm. Is Peter paranoid? ‘The paranoid man is simply the man with all the facts.’ Anonymous

Paranoia at its finest

Freidkin unleashes a totally original and riveting psychological drama. The symptoms of this story frantically spread and feed off your mind in frightening fashion. A psychotically sick tale that plagues you with themes of loneliness, desperation, and mental instability. Plus it lightly touches on notions of government control and the devastating effects of war. Such a great film, one that might come off as ridiculous to some as it blazes an unfamiliar path. But for open-minded movie watchers ready to be challenged, this is must-see stuff.

BUG is a wonderful descent into paranoid and persecutory delusional disorders.

Strange in several ways, but so is the topic: paranoia

The interesting thing about it, for me, is that it highlights the fact that we all have weaknesses caused by the pain in our lives, and if you are unlucky enough to meet someone who reinforces those weaknesses, it is a fairly short trip to trouble.

So glad I’m not paranoid and/or dillusional.

It’s also very strange, although I suppose that’s only to be expected considering that the film is adapted from a play about two characters who spend most of their time inside a motel room feeding off each other’s paranoid delusions (not the most delectable entrée).

Bug is a portrait of two borderline schizophrenics. It’s a love story featuring two lonely paranoid delusionals who afflict each other with their troubles. They concoct wild conspiracy theories to explain the bugs – everything from aliens to government cover-ups and secret medical experiments. Their situation becomes characterized by an “us against the world” mentality as they grow convinced that everyone else is involved or connected. When a psychologist stops by to visit Peter, he is viewed as a spy, and is not to be trusted.

The movie, directed by William Friedkin (whose previous credits include The Exorcist and The French Connection), never tries to convince us that Agnes and Peter’s delusions might be real – that this could be the story of two unfortunates caught in the grip of an unethical experiment.

Weird, but somehow compelling movie about people descending into a shared madness in a motel room in the middle of nowhere.

The film refuses to be a clear-cut study of insanity; there’s a subtle brilliance to the way Friedkin explores uncertainty and panic, as if to say that we’re not meant to have all the answers… every behavior in this film is overwhelmingly irrational.

In my opinion, “Bug” is totally about paranoid-schizophrenia and its ablity to spread from one person to another. But watching “Bug” carefully on another level, one is given no evidence why the terrifying scenario could not be real. Are Aggie and Peter nuts? Or is there an evil government experiment going dreadfully wrong? It’s all up to you.

Somebody plays on the weakness of another with a wild notion and pretty soon both believe something that’s not real.

…both of the main characters were bonkers.

…the main idea of the movie is mental illness.

…mental people coming together in tinfoil and bug lights with a truckload of mental paranoia induced.

…mostly the film relies on atmosphere and paranoia. And paranoid it is. If you are at all worried about governmental intrusion, psychotic breakdowns or other neurotic tendencies–this is probably your ticket to the loony bin.

…There would be brief clips of bugs squirming around; those brief clips helped show you what Agnes and Peter were seeing, especially under the microscope. But, they weren’t real.

This guy thinks he has bugs and he’s manipulated this woman to think she has them too. That’s the idea, not that “this isn’t even about bugs” or “this isn’t horror” or “where are the monsters and action”. It’s a psychological thriller. You’ve got to think deeper than just what’s given to you in the film. The idea is to leave you with thinking that, if you’re not careful, anyone can manipulate you, just like Jim Jones and just like Peter did with Agnes.

The bug infestation does exist, however, in the minds of the two characters. Brilliant.

It’s an unflinching portrayal of a couple’s descent into madness. Or is it? You may not be absolutely certain, because there are a few suggestions along the way that the couple’s paranoia – their conviction that bugs have been implanted in them, that Government agents are experimenting on them – may not be total hallucination. Here Ashley Judd is all too ready to buy into her new boyfriend’s delusions because she has been lonely and his companionship is a lifeline.

It is a story about one lonely woman’s descent into utter madness…led there by a man who is already quite insane himself.

With the sounds of helicopters and the searchlights, the viewer is treated to vision of true madness.

The plot was never interested in focusing on logistics, and rightfully so. We’re now fully immersed in the delusional world of two people who were made for each other, a world in which nonsensical ramblings make perfect sense.

The last ten minutes of the film have both Judd and Shannon delivering high-intensity speeches that almost come off as poetic in a twisted sort of way; their words point to an explanation only they can understand, and in turn offer a solution that only they see as appropriate. (long and literate)

William Friedkin shows once again that he is a hungry talent to be reckoned with; his films always remind us that we can never quite know what goes on, not with absolute certitude, and that some of the most

momentous events leave us not with truth but with more questions.

Peters monologue at the end of the film made me want to memorize it for myself and go around repeating it to my friends just to get a laugh.

This film is about Crack. Crack and crack addiction.

Even a psychologist who comes in to try and help Peter is damaged in that he’s hooked on cocaine himself and seems only passively interested in telling the truth.

a true descent into madness.

The final third of this movie is about as intense as I’ve ever seen, Peter tossing off lines that mix the People’s Temple, Tim McVeigh, Ted Kazinski, etc., in a flourish of deep conspiracy driven insanity justifying everything, and Agnus locks in and has a wonderful sequence in which she pieces together a wild reason for the loss of her child and more, at the insistence of Peter’s relentless prodding; it’s almost as if they become one character. (Actually, it’s almost as if she takes over; Peter even looks almost scared of her when she takes control.)

What’s unsettling about it was watching a man’s descent into madness and watching him completely lose touch with reality.

Before long Agnes’s own loneliness and desperation lead her to believe him and she soon begins to see the bugs that are not really there.

I’ve worked with schizophrenia patients for the past 10 years, many of whom are paranoid and speak very similarly to Peter. While I find it offensive their lives are often made into horror movies, I did not take offense to “Bug.” I take more offense to whoever decided to market it as a horror film, instead of a disturbing look at a situation that can be very real.

Be it the fear that someone is lurking behind you in a dark parking lot or a bug is crawling on you while you sleep, there is a bit of paranoia in us all. The little seeds of fear planted in our minds by rumors and suspicion grow as we try to fill in the irrational gaps.

Freidkin unleashes a totally original and riveting psychological drama. The symptoms of this story frantically spread and feed off your mind in frightening fashion. A psychotically sick tale that plagues you with themes of loneliness, desperation, and mental instability. Plus it lightly touches on notions of government control and the devastating effects of war. Such a great film, one that might come off as ridiculous to some as it blazes an unfamiliar path. But for open-minded movie watchers ready to be challenged, this is must-see stuff.

Bug is a parable about madness, first generated by obsession with insects (as in the title), then degenerated into total paranoia towards whatever surrounds the protagonist (a great Michael Shannon ): the man, a veteran, will drag into the abyss along with him, even the woman with whom he has an affair.

The director, William Friedkin, makes a very good film, which will keep the tension high throughout its lifetime.

The edition in question, however, is devoid of any interesting special content. Merit

Do you ever wonder if some movies are made so actors can demonstrate extreme behavior just to see if they can pull it off? I have worked in healthcare for 20 plus years and have worked with many people patients or otherwise with very altered versions of what most perceive as reality. I applaud the performances but the plot doesn’t draw me into to believing this is a possible story line, probably because my education and experience hold me back. I don’t regret watching it once but won’t do it again.

Wow! That was a crazy insane movie. So glad I’m not paranoid and/or dillusional.

Movie about people descending into a shared madness in a motel room in the middle of nowhere.

Mental illness is more terrifyingly real than monsters or alien invasions

certainly the best thing i’ve ever seen about folie a deux [shared insanity], and i HAVE dated a paranoid schizophrenic. bad dreams tonight…

Really stupid movie, however, it did show how manipulating and convincing some people are and are rampant at destroying other people’s lives.

This movie is really not a horror movie at all. It is a moving depiction of two people’s descent into a folie a deux, and very well done. [Obviously educated to know the term, which I had to look up]

: One person’s delusion becomes the other person’s delusion. One person’s problems become the other person’s problems, much like a love affair.

With mounting urgency, she begins to share his obsession with bugs, and together they hurtle headlong into a paranoid fantasy that ties together in one perfect conspiracy all of the suspicions they’ve ever had about anything. (Ebert)

From Plugged In: Ashley Judd falls prey to the delusions of a paranoid man plagued by his belief that the government has infected him with flesh-eating bugs in this hard-R thriller.

Who was the “doctor”? you try to figure out and then are often surprised at the ending, but it’s plausible because there were little things along the way that feed into that twist. If you try to figure out this movie, you might as well turn left and wander out into a field.

This is one of the finest expressionist films I have seen. While the subject matter is extremely grave, the film does such a wonderful job of immersing you in to the world of the paranoid schizophrenic; a delicate balance between sane and insane.

! Shows how easy it is to slowly manipulate someones thought process. [he refers to Peter manipulating Agnes]

Mental illness is more terrifyingly real than monsters or alien invasions.

certainly the best thing i’ve ever seen about folie a deux [a shared psychosis), and i HAVE dated a paranoid schizophrenic. bad dreams tonight…

it did show how manipulating and convincing some people are and are rampant at destroying other people’s lives. [In other words, Peter destroyed Agnes]

I almost stopped watching it early on, but simply got drawn into the two lead actors’s disintegration and complete break with reality.

Wtf did I just watch? Two paranoid delusional people shacked up in a hotel room???? Very weird for three well known actors.

If you enjoy bringing your brain to the theater and leaving the popcorn at the counter this is for you.

If you did not know what delusions of parisitos was, you would not “get” this movie. I have dealt with many people with this condition. [So here we have ‘an expert’ on people with ‘that’ condition!]

what happens is horrific, but it happens in the mind of Ashley Judd’s character.

and psychological parody of society and the military especially with all the PTSD and delusional parasitosis going around. [Yes, and ‘conspiracy theories’ are going around too!]

A realistic look at schizophrenia.

Gave me the creeps. Everybody’s nuts.

I didn’t like how it made those with mental health issues look bad

OKAY, ENOUGH IS ENOUGH (I HAVE PLENTY MORE)!

If you found this essay worthwhile, consider contributing $3.25 a month (for ‘gas money’). I might need it after this! (Or buy a DVD of a Water Time rough cut.)

51 comments for “An Open Letter to William Friedkin & Tracy Letts (authors of ‘Bug’)”