Note: If I posted a version of this a while back and forgot, my apologies. Ditto to those who have already read it in my last memoir, Can’t You Get Along With Anyone? A Writer’s Memoir and a Tale of a Lost Surfer’s Paradise.

The photo-with-text book I’m working on will contain excerpts from my three books, which excerpts will be chosen for a stand-alone quality but mainly because I have good photos to go with them. Such is the case with the following, which is the prelude to my investigation into the murder of American expat Max Dalton, who was assassinated by organized squatters at Pavones, Costa Rica in 1997. (The piece was written for Men’s Journal magazine, but that’s another story on its own. As with my Election Night in El Salvador essay, the story was killed for political reasons.)

This format is not the best way to demonstrate how the book will look due to the limited layout here; many of the book photos will be full page, plus there is nothing like hard copy, and so on.

#

A NIGHT AT THE CANTINA

Backstory

Back in 1974 Danny Fowlie had it all. Well, almost. Danny was a very wealthy man, a spectacularly successful contrabandista, his specialty being multi-ton loads of marijuana driven, flown or boated north from Mexico, plus freighters-full of Thai sticks. Aside from his flotilla of yachts and miscreant-manned fishing boats, his private aircraft, innumerable big- boy toys and trinkets, personal extravagances and priceless artifacts from primitive cultures worldwide, he owned, or would soon own, a multimillion dollar farm in Riverside, California, a ranch in Baja, Mexico, plus fugitive financier Robert Vesco’s splendiferous, heavily-fortified compound in San José, Costa Rica; and Danny, toting a suitcaseful of gringo green, was poised to possess the one thing he did not have, but wanted most – his own private piece of paradise, a far-flung Shangri-La which he would benignly rule, and share with his entourage of spooky hipster-savant cronies and hangers-on, plus assorted living legends of the surfing subculture.

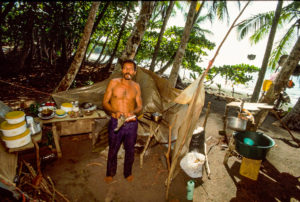

There are two ‘ends of the road’ in Costa Rica, Puerto Viejo on the Caribbean, Pavones on the Pacific. This is the former. I’m guess I’m attracted to ends of the road

Apocryphal or not, my favorite discovery story (there are a few) goes as follows: One day, while on a scouting mission by air out of the old Costa Rican banana port of Golfito, Danny overflew a remote tract of land at the mouth of El Golfo Dulce in far southern Costa Rica near the political technicality of the Panamanian frontier. Unreachable except by boat or horseback along the unsullied, palm-girded beach, the tableau below him appeared to be exactly what he was looking for. Riffling, clear water rivers snaked down from the high reaches of the inland rainforest (wherein still lived stone age aboriginals) onto a fecund littoral plain that would be ideal for the growing of food crops and the grazing of livestock. The inshore waters, Danny knew, given the coast’s isolated location at the mouth of the broad, unpolluted “Sweet Gulf”, would be teeming with fish.

But there was something else down below along that shoreline that day and it riveted Danny’s attention and no doubt made him blink in disbelief, heart racing. He no doubt told his pilot to circle back and descend for a closer look. And it would be hard to imagine Danny not – at some point as he stared wild-eyed out the side window of his plane, nose pressed against the glass – hooting in unbridled glee as the implications of what he saw settled in.

The wave Danny discovered that day would become legend in the surfing world; a wave that wrapped along the shore from the jagged, rocky point at the mouth of El Rio Claro in the province known as Pavones then peeled endlessly into the bay, a rocket left slide ride-able for nearly one mile on good days.

Danny Fowlie did not do anything in a small manner. Using the official and clandestine sources he’d cultivated, he bought the whole shebang, over 6,000 acres, including much of 12 miles of stunning beach front. By barge and tugboat Danny hauled in heavy equipment, building materials and generators, along with foodstuffs to sustain his crew of Costa Rican laborers and imported agronomists, veterinarians, oceanographers and engineers, until the farms and fishing boats he envisioned could start producing and make the community he foresaw self-sustaining. Danny cut roads, at first only within his kingdom, demurring on the idea of a direct connection with the outside world; bridges soon spanned the plethora of rivers and streams descending from the inland rainforest; the deep seaside bush was cleared for a private airstrip; schools and churches were built; farms sprang up, overseen by experts in soil and crop management. Danny built what he dubbed The Clubhouse on the property known as The Sawmill, a three-story manse a couple of kilometers down the coast from The Point, and which overlooked its own perfect wave.

And another thing Danny built was the cantina, a private watering hole overlooking the point wave at Rio Claro, where he could kick back with his surf buddies and Underground Empire sidekicks and exult in what he had created.

Yes, Danny, build it, build Dannyland… and they will come.

“You gotta picture what it was like back in the beginning,” my Long Island surfbuddy Dave Ferraro told me. Dave and his brother Ben had come to Pavones in the late 1970s, at the beginning of the Fowlie era.

“We’d sit in the cantina after riding these perfect waves on this wild, stunning piece of coast,” Dave went on, grabbing my arm, so jazzed at the memory, “and here comes a couple of Danny’s vaqueros on horseback, they’d ride right up to the bar and order a brew, a cold one if the generator was working. Wide-brimmed straw sombreros, lariats, six shooters, bandoleers stuffed with bullets… picture it! I mean it was the frontier, man, almost inaccessible, an adventure just getting there… with no authorities… you could do what you wanted. My friend, your imagination could go wild in a place like that…”

And all was well in Dannyland in those early years, indeed, for a full decade, until 1985, when el excremento hit el ventilador with a vengence, and the imaginations of a lot of people went wild. And a lot of people did what they wanted.

#

A Night at the Cantina

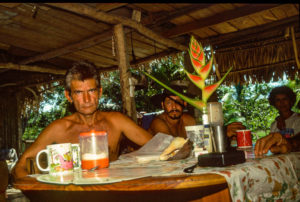

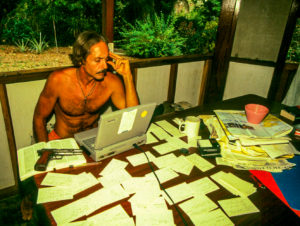

The cantina, 1997, a few months after electricity came to Pavones (and ruined the place, as some would say).

January 21, 1998

“All our lives are in danger,” the basso gringo voice says when Billy Clayton hands me the cell phone at the cantina bar at some point between dinner and my third Pilsen. Billy wishes me happy birthday and sets me up with a rum shooter on the house, but I’m too distracted by the bizarre phone greeting to thank him.

“Who is this?” I inquire.

“I’d rather not say,” the phone voice says.

“Where are you?”

“Nearby… but not… too near.”

“How did you get this number?”

“The embassy.”

There being no land line to Pavones, I left the cantina cell number with the embassy people up in San José in case… just in case.

“What do you mean `our lives are in danger’?” I want to know.

Then, recalling that this bulletin is pretty much old news: “I mean, specifically?”

“Listen…” the lowered voice says, basso verging on profundo now. “If you want the real story about what happened to Max Dalton… follow the money.”

Wait a minute, I’m thinking. I’ve heard this dialog before… while munching popcorn in a multiplex somewhere. I suppress a giggle. I mean, come on.

“Five point two million dollars from Union Europa for the southern zone.”

“Huh?” Follow the money.

“At least a million dollars to Gerardo Mora and his precarista movement.” Mora is the local squatter – precarista

– leader who was present at the shootout that killed Max and Alvaro Aguilar, and who was briefly detained as a suspect in the crime.

“Look,” I say, still racking my brain for the name of the goddamn movie.

“Why don’t we get together sometime?” But the line has gone dead.

Billy Clayton is leaning over the radio by the register, trying to catch the news from San José maybe; I can hear staticy Spanish over the bar noise. A stateside story broke today, I hear. Bill Clinton in hot water again, something about some salacious doings with a White House intern. Maybe Clayton cares, but I have my own intrigues to deal with here and now, plus this 21st day of January, 1998, is my goddamn Big Five-Oh, a potentially stress-producing benchmark, especially for someone whose life is… well, is what it is. And this week-long flat spell – a result of some mid summerdoldrums in the Southern Ocean – isn’t helping.

The phone call.

My thought is that the call was a prank. The fact that I’m investigating the killing of Max Dalton for Men’s Journal magazine is common knowledge in this remote little gobbet of paradise, and although all the norte expatriate residents knew and liked Max, a certain blackly comic slant prevails, and naturally so; it helps take the edge off the chronic uncertainty of the precarista situation. Plus that deep, gravelly voice could’ve been disguised… plus the goofball movie allusion…

All the President’s Men. Right.

The question is, which one of my motley crew of compadres slunk off to make the call?

I scan the cantina to see who’s missing from my birthday festivities. Clay has a cell phone up at his Punta Banco hideaway and is something of a demented jokester, but he’s currently two barstools down in besotted conversation with Mountain Mike. The two are reminiscing about Clay’s terciopela encounter a couple of years ago in the bush at Altamira. I’ve heard the story before. Clay’s leg had turned plum-purple right up to his groin from the snake’s bite, and Mountain Mike, with input from an Indian bruja, had concocted a tea from roots and tree bark that counteracted the venom. Still, Clay had spent three days in a hutch in the hills, racked by convulsions, while la bruja tended him.

No, wasn’t Clay.

Alex? Alex hasn’t moved from his usual corner stool, nor has he apparently missed a beat in his rap about the seraphic inter-dimensional beings he occasionally converses with, especially after a rip-roaring surf session has sufficiently heightened his metaphysical percipience. According to Alex’s cosmology, flitting around the earthly firmament are vibrational traces of the consciousness of past dwellers of any given space, and these “mindbits of bros past” will interact with the inter-dimensional beings, as well as with the consciousnesses of current space-dwellers. Something like that.

Tonight the unlikely victim of Alex’s ramblings is Carlos Lobo, Danny Fowlie’s former right hand man from back in the day, variously described as a “one man army”, “crazier than a drunk Hawaiian”, “a sufferer of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder” (from the year he spent holed up in his house, defending it against continuous precarista snipering, drive-by shootings, bomb-throwings and ground assaults), and – by my buddies, Erik and Joachim – as “the straightest, most loyal man in Pavones.”

Carlos? Carlos speaks not a word of English. No, wasn’t Carlos.

Erik and Joachim? The caller had mentioned the embassy as the source of the cantina phone number. Erik and Joachim know about my embassy visit, my intelligence sharing with the State Department, but they’re here also; I’ve just had dinner with them. Who else knows about my embassy visit? No one. No one I know of.

Whoever made the call knows.

How about Logan, Derek Logan, locally known as “the fool on the hill” (for the elevated location of his command post/domicile) or, simply, “the nutcase,” who has already made it known that my meddling presence in his bailiwick pleases him not a bit? Logan never, ever, sets foot in the cantina. Billy Clayton’s cantina.

Shit.

I hope it wasn’t Logan.

Now I’m thinking the call was probably not a prank… I’m thinking that the Union Europa tidbit was too out of left field for the conversation not to have been the real thing… Union Europa. Some sort of international banking crew. Follow the money…

Gerardo Mora. The voice had mentioned Mora as the beneficiary of Union Europa’s munificence. Nobody around here jokes about Gerardo Mora.

No, definitely not a prank. But it still could’ve been someone I know, a Pavones norte who somehow found out about my embassy visit and wanted me to have the information… but did not want to involve himself in the Dalton matter, probably out of fear of retribution from Mora.

Erik and Joachim have warned me about what might happen if Mora learns how much I’ve uncovered about the day Max took a bullet in his chest. Further cautioned that if Mora and his men come for me, it will be from the river side of my house (which is primitive and except for the bodega, or strong room, cannot be locked). Suggested that I sleep in my camper, which is parked in the yard, because these men most likely won’t think of that, and that I should keep the Browning 9mm Erik lent me within reach at all times.

And of all the players actively involved in the land conflict in Pavones, it’s Erik and Joachim – with their dead of night retaliations against the most militant of the squatters during the two-year period in the mid-90s when the land war here last reached flash point – that I should listen to in matters of personal safety.

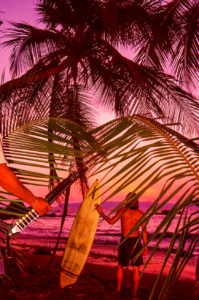

Erik and Joachim: the two in camo and blackface roaring down the rutted dirt track between Pavones and Pilon in their stripped vintage Land Cruiser, quivered-out surf racks tagging them as warrior/waveriders, on moonless nights their headlights and million-candlepower spot the only illumination for 20 ks on this wild, lawless coast (no electricity back then).

The two scanning the dense, ink black bush of potential fields of fire, popping off rounds from their AK and sawed off twelve to let the Down South world know that of the remaining norte landowners who hadn’t been driven off by precarista intimidation and outright violence, there were a couple left who were out there ready to rock and roll, maybe kick some ass of their own.

Surely, these guys know whereof they speak. So I have taken certain precautions, although I still sleep in my upstairs sanctum overlooking El Rio Claro.

Billy Clayton sets up fresh Pilsens as Alex sidles over, wishing me a “Happy birthday, dude.” I hand the phone back to Billy, who has abandoned the radio and is now eyeing me as if to ask who the caller was. Had he not been the one who handed me the phone in the first place, Billy would have been my first choice as to the caller’s identity. With the possible exception of Erik and Joachim (hard to say one name without the other – a Rosencrantz & Gildenstern kind of thing), he is the most knowledgeable of the resident nortes regarding the various intrigues of the land conflict here, albeit the most skittish.

Billy’s problems started on the morning of September 16, 1991, when Costa Rican Hugo Vargas was gunned down, the first death in the squatter wars. A fired up mob had stormed a norte surfer’s oceanfront property just south of El Rio Claro and the panic-stricken caretaker had opened fire with a buckshot-loaded scattergun. Vargas had been killed on the spot, another campesino severely wounded, gut shot. Billy had run the gauntlet of enraged squatters in his van torescue the caretaker and his family; then, that night, after the cantina had been surrounded by a machete-brandishing mob, Clayton fled Pavones, hiding under a tarp in the back of a truck. He would not be able to return for a year.

“Look, we’d all been warned that a gringo was gonna get bush-whacked,” Billy told me a couple weeks ago over a Pilsen at the cantina, after claiming the Dalton killing was a setup. “It was just a matter of who. There was a hit list… Max was on it… I was on it.”

“Who warned you?” I’d wanted to know, but Billy stood up suddenly and turned seaward, shaking his head as if he’d already said too much. The wave in front of the cantina that day was shoulder high and Billy and I watched a hot local kid named Meco rocket by as a distant thunderhead morphed surreal and vaguely angry, spouting veined lightning over the pristine Osa Peninsula across El Golfo Dulce (The Sweet Gulf).

“On a certain level…” Billy muttered, and I was not sure whether he was addressing me or simply having a thought that had inadvertently found voice. “…it was the wave here that killed Max.”

So true. Without that miracle of a wave roaring in from the southern latitudes, none of this would be here, not the settlement, the farms, the fish camp, the school, the churches, the roads and bridges (such as they are), the cantina itself. Nor the people, the expat nortes who have settled here looking for their own little piece of paradise. And nor would the squatters, the precaristas, be here, looking to take it from them.

And, certainly, absent that wave nor would I be here, contentedly settled in after well over a year of wandering the coast between Tijuana and the Panamanian frontier.

“Don’t worry about it, bro. Probably just another harmless whacko,” Alex says after I run down the basics of the clandestine phone call, although I omitted the vital detail of the caller’s mention of the embassy. “We got our share of whackos around here.”

I have to smile at that. Much as I like the guy, Alex himself has been known to evidence some peculiar thought processes, even aside from his goofball cosmology. He’ll expound at length on his deep involvement in the postmodern peace and brotherly love movement, then, with nary a connective, suddenly be discoursing on the merits of

the Chinese version of the AK-47 assault rifle and the design subtleties that make it less likely jam up in adverse bush conditions on full automatic, while the inferior Czech model will likely fail. That, or the artistry involved in constructing a pipe bomb with a uni-directional blast locus, and how to position the device to blow a big enough hole in an inch-thick bank vault to reach through to grab the goodies.

All this while looking like a fugitive from the rock band Kiss. Alex is in fact not a gringo, but a Mexican national, although his English is flawless. A former Tijuana gangbanger, Alex escaped the perils of that dead end through the surfing life; he ducked south to Pavones some five years ago, toting a hollowed out surfboard packed with cash to buy land with and an assortment of weaponry with which to defend that land.

When I pointed out the possible inconsistency implied in his commitment to pacifism while simultaneously surrounding himself with the tools of warfare, Alex frowned at my failure to see the larger picture. “We are all bros, bro,” he replied, “but if a bro fucks with you, you got to be ready to wax his gnarly ass, post haste.”

The cantina is starting to cook as representatives of the various Pavones factions materialize from the surrounding bush and attach themselves to cerveza bottles and plastic cup rum shooters. Wenste and his cabal of precas-at-the-point are outside by the seawall, Wenste looking as mean- drunk as usual under his straw sombrero; he’s probably packing weaponry under his tattered guayabera. Luis, another squatter, albeit of considerably mellower disposition than Wenste, and a buddy of mine – he’s nicknamed me Malo, Bad, which I admit I kind of like – wishes me feliz cumpleanos and insists on buying me another Pilsen, although by now I’ve made the move to cane juice.

El Gitano (the Gypsy) is cross-eyed drunk and running amok at the bar with the money I gave him this morning. A.k.a. El Brujo (The Sorcercer), Mal Ojo (Evil Eye), El Gitano is a binge-type alcoholic, self-professed dabbler in the occult and accused child molester. I’ve hired him as my link to the precarista movement. Everyone, nortes and Ticos alike, has warned me about him, saying he’ll turn on me in a heartbeat. But it was El Gitano’s introduction to Gerardo Mora that was my first breakthrough in the Max Dalton investigation. El Gitano, of course, is a preca himself.

Maybe half the cantina crowd tonight is of the preca persuasion, ranging in mien from mellow to not-so-mellow to outright nasty. Gerardo Mora himself is perhaps conspicuous by his absence: he and his crew keep to their own territory just up the road at Langostino. Nevertheless, the vibrational mix is edgy, with some former and even current enemies occupying adjacent bar stools.

The cantina, being the only watering hole within many miles, is de facto neutral territory; those who enter here have an unspoken agreement to temporarily put aside their quarrels. Still, with the nearest real police presence a good two hours away (if the road in is passable and the bridges intact), the so-far lack of outright bloodshed (fist fights are common) is in my view something of a miracle. I can’t help but wonder, however, how Billy Clayton – a human lightning rod in the land conflict here – feels as he serves malvados who not so long ago waved machetes in his face and threatened to dice his gringo ass into fish chum, and who just might be sitting at the bar, his bar, planning his demise.

Squatter campsite on land legally owned by a Norte. I got hit by a thrown rock a couple seconds after snapping this.

Alex has wandered off so I return to my table, join Erik and Joachim. German expat Joachim Gerlach is a former European stunt driver, occasional jewel thief and all-around international scammer whose connections run the gamut from the Israeli Mossad to the most vicious criminal organization on the planet, the Bulgarian mafia. His partner, Erik Reinhold, is a Dutchman who came to Pavones “because of an Arab with a knife…” The story gets better from there, its upshot being that the fellow’s knife was no match for Erik’s gun.

After spending a year in prison, and seduced by his buddy Joachim’s idyllic accolades of the down south surfing life, Erik arrived innocently wide-eyed and ready to unwind in the lineup, but within days found himself armed to the teeth at a dead-of-night bridge blockade, looking to bushwhack the squatters who stole Joachim’s $30,000 grubstake.

Having committed themselves to fight the precas on their own terms, Erik and Joachim’s lives got nothing but crazier from that night on. I’ve become tight with the pair over the seven months since the battered old rig I call La Casita Viajera first rumbled down the dirt track to road’s end, the search for my long-missing old friend, Christopher, a.k.a. Captain Zero, having come to its disorienting denouement. With respect to the Dalton matter, they have in fact become my confidants. Although I have other friends amongst the Pavones expats, it’s these guys I trust, and, I believe, vice versa. And trust is everything down here.

I tell the boys about the phone call, the cryptic missive from my down south Deep Throat. Erik, who is the more sanguine of the two, smiles at the spy-vs-spy theatricality of the affair. Joachim does not. “Listen, my friend,” he says in his light German accent. “This is a box of snakes you’re dealing with.”

Yeah, right!

“The Union Europa connection is interesting,” Erik muses, ever more analytical than his volatile partner and brother in arms. “Maybe it’s not just the Dutch who are financing Mora.” The fact that his countrymen, through their embassy, have been funding the squatter movement is a sore point with Erik, especially since Max’s death. He and Joachim were close to Max, had for a time acted as his bodyguards.

“I’ll ask Mora about Union Europa,” I say. “I have another meeting with him in a couple days.” Between his leftist diatribes and mendacious punditry on the history of the Pavones land conflict, Mora has been letting a lot of vital information slip, especially if I’m careful in directing the drift of our talks.

“Listen to me,” Joachim says, leaning forward, voice lowered. “You’re going to go up to the bush at Langostino one too many times. And it won’t be messy, like what they did to Max. It will be just poof! – hey, where’s Allan?”

“I don’t think they’d actually kill him,” Erik opines. Over the past couple of weeks Erik has been vacillating with regard to the degree of possible peril I’m subjecting myself to in my relationship with Gerardo Mora.

The two argue the point in what sounds like a conglomeration of Dutch and German. It gets heated. Finally, I request that they maybe include me in the discussion by reverting to English, since it’s the possible future of my ass they’re debating. But they simply shut up, Erik sighing, Joachim red-faced.

“If he’s careful, he’ll be all right,” Erik says, blithely sipping his rum and looking around, bored with the conversation now.

“Hey, man. Happy birthday,” Joachim says, hoisting his rum.

I return his grin. That’s right. The Big Five-Oh.

I look around at the cantina crowd, something out of early Peckinpah as updated by Tarantino. If I’m thinking a candle-festooned cake is about to be wheeled in followed by this lot breaking into the birthday song, well, I’ve got another think coming. No, Dorothy, you’re not in… well, even in Baja anymore.

If Alex’s notion that we leave vibrational traces behind us in our earthly travels is correct, surely the cantina – this ramshackle wrinkle in space- time – would be bubbling the ether tonight. Whose phantasmal vibes are even now pulsating through the celebratory continuum of my Big Five-Oh, colliding with those of this oddball mix of multinational vagabonds and terror-bent locals? Who that has come before is now missing?

Max is gone, of course, shot down on his own land that drizzly November day and left to die while a precarista mob taunted him.

Gone from paradise.

And how about Owen Handy, the Vietnam vet brought to Pavones in the late 1980s to teach weapons and hand-to-hand combat techniques to those nortes who hadn’t already been driven off by preca violence? Although Handy’s courage in battling the most violent of the squatters is undeniable (he’d stood his ground in full-blown firefights in which automatic weapons were used against him), the pressure of living in a guerrilla war environment had eventually driven him over the edge. He’d psychologically survived the trauma of Vietnam but the pressures he had been subjected to in Pavones precipitated a descent into greed and drug addiction.

Gone from paradise.

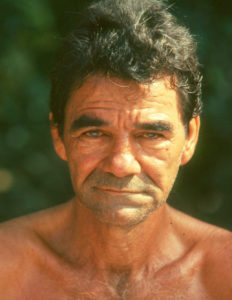

Gerardo Mora, his brother-in-law Carlos Araya at their Langostino compound, a short jounce up the dirt road from Pavones.

Or the Right Reverend Loren Pogue, the gringo expat whose fiduciary schemes ran the gamut from hilariously in-your-face land swindles to cocaine trafficking to the black-market baby business, and who boozily oversaw his nutso enterprises from his banana port brothel. (His business card proclaimed him the proprietor of a local home for unwed mothers.) Perhaps best known locally for having shot an unarmed precarista in 1989, the Reverend is currently serving a 27 year sentence in a stateside prison for… well, you name it.

Likewise gone, gone from paradise.

Or how about Winfred Zigan, who, like some Bob Hope From Hell, would catch and eat assorted cantina bugs (the bigger and crunchier, the creepy-crawlier the better) to entertain the beer-guzzling expat troops on bleak and womanless post-surf session nights? Winfred fled Pavones in 1992, not because he’d recently been shot in the head in a squatter-related tiff (a mere crease of the scalp), but from disgust when completion of the dirt track from Golfito began to afford easier access to Pavones for the multitudes Up North. In Winfred’s view, the squatter wars were a minor nuisance. That which, well, bugged him, was his perception that Pavones was getting civilized – notwithstanding the fact that electricity had still not yet arrived at the still barely-accessible end-of-the-road hamlet.

Winfred elected to beat cheeks further south (the natural direction of vanishment), but since the road ends here, his escape was by sea. Rumor has it that he is now the lord and master of his own otherwise uninhabited island somewhere off the coast of Panama, his battlements no doubt directed seaward, protecting the sanctity of his own private perfect wave. (Winfred would approve of the State Department travel advisory urging U.S. citizens to avoid the Pavones area, for how it has kept the surf lineup uncluttered with those uncommitted, here-on-a-two-week-surf-vacation lightweights he so detests.)

No, not gone from paradise. On the contrary, Winfred has only dug in deeper.

How about the itinerant Aussie who was strung up here in the cantina for some now-forgotten, surf-related faux pas back in the early 80s? Bound and gagged, noose tautly rising from his outstretched neck to an overhead rafter, he’d been left teetering on a bar stool while the boys hoisted brews and staggered around, occasionally bumping him to test his balance. He’d eventually been cut down, patted on the behind and informed he could go now.

Definitely gone from paradise is that discourteous Aussie, but what sort of jagged, get-me-the-fuck-out-of-here vibrational traces linger?

Just one more, and I save the best for last.

Long gone from paradise is Danny Fowlie, to his new home stateside at the Terminal Island Federal Penitentiary.

Danny. The Waterman Who Would Be King.

#

Addendum: Anyone who wants to read the full investigation can do so via the free PDF in the sidebar, starting on page 180.

Donations are welcome via PayPal or Moneygram via the Coos Bay, Oregon outlet. (Search ‘Moneygram’ if you don’t know how.) If you use this method alert me via allan@banditobooks.com.

Also, if you liked this one and didn’t catch Election Night in El Salvador, you might give it a look. There are similarities.

48 comments for “A Blast From The Past”